rivett608

Diamond

- Joined

- Oct 25, 2002

- Location

- Kansas City, Mo.

Christopher Polhem (1661-1751) was a brilliant engineer....... they had a room devoted to him in the Tekniska Museet in Stockholm....

In the exhibition you find Christopher Polhem's cutting machine for making cog wheels for clocks. It is counted as the world´s first automated machining tool. At the beginning of the 18th century, Polhem operated a manufacturing works in Stjärnsund in Dalecarlia, a province of Sweden. In addition to the cog wheels, the works made plates and locks using automated machines.

The Mecanical Alphabet

This exhibition also displays Polhem´s Mechanical Alphabet, a number of wooden models that describe a range of technical design elements. The Mechanical Alphabet was used in teaching at the Laboratorium mechanicum – Sweden´s first school of technology – and later also at the Institute of Technology, the predecessor of the Royal Institute of Technology of Sweden (Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan).

http://www.tekniskamuseet.se/1/864.html

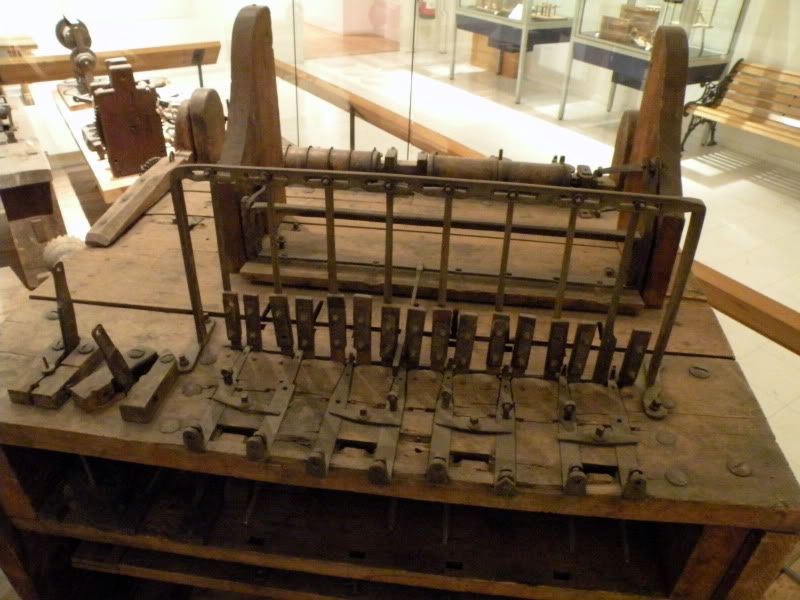

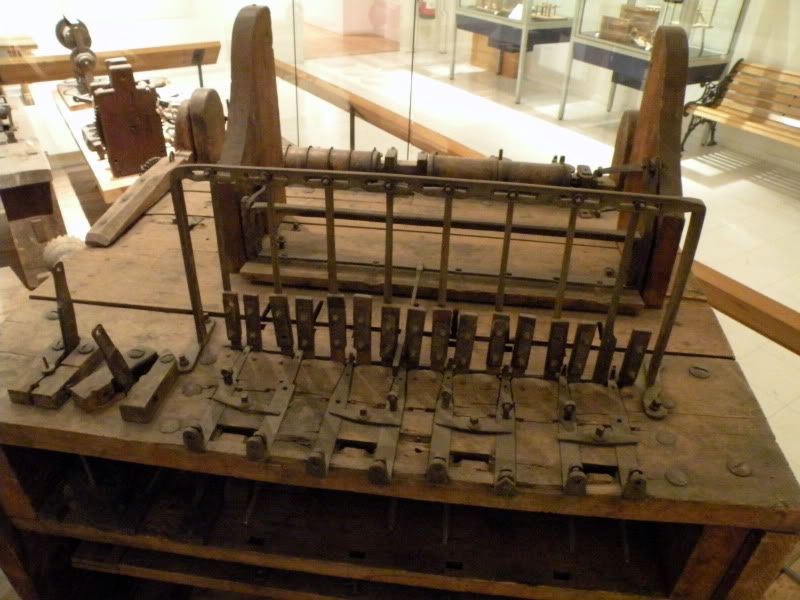

Here is his Automatic gear cutting machine...... sort of early CNC.......

The cutting spindles.....

The brian box......

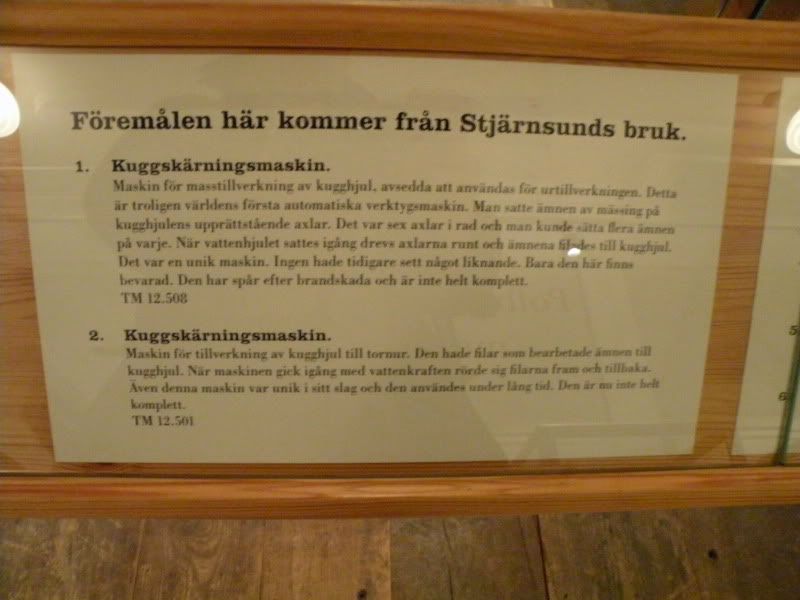

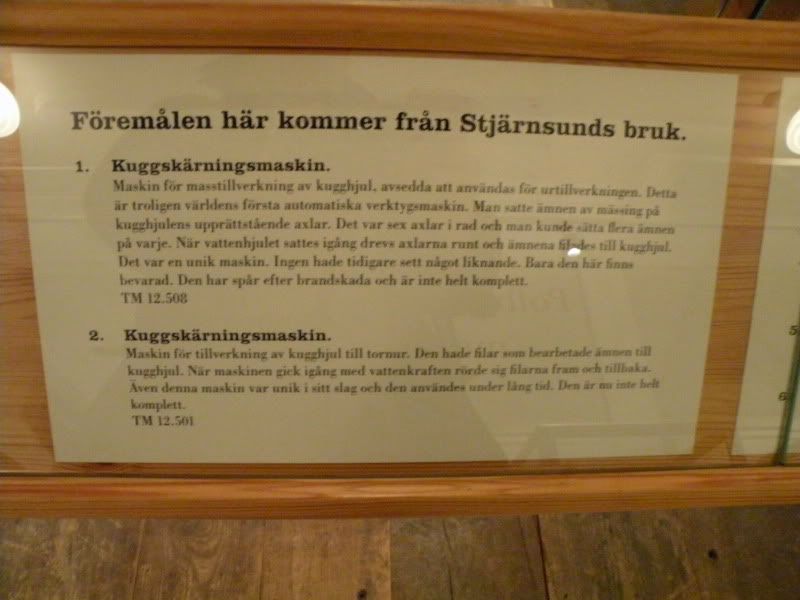

Description in Swedish.....

In the exhibition you find Christopher Polhem's cutting machine for making cog wheels for clocks. It is counted as the world´s first automated machining tool. At the beginning of the 18th century, Polhem operated a manufacturing works in Stjärnsund in Dalecarlia, a province of Sweden. In addition to the cog wheels, the works made plates and locks using automated machines.

The Mecanical Alphabet

This exhibition also displays Polhem´s Mechanical Alphabet, a number of wooden models that describe a range of technical design elements. The Mechanical Alphabet was used in teaching at the Laboratorium mechanicum – Sweden´s first school of technology – and later also at the Institute of Technology, the predecessor of the Royal Institute of Technology of Sweden (Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan).

http://www.tekniskamuseet.se/1/864.html

Here is his Automatic gear cutting machine...... sort of early CNC.......

The cutting spindles.....

The brian box......

Description in Swedish.....