speleoflutist

Plastic

- Joined

- Aug 7, 2005

- Location

- Worton, Maryland

Just acquired a new (to me) E. Gould and Eberhardt shaper. This is how the name appears in the main frame casting. I have not been able to locate any serial or model numbers yet.

It was discovered by a neighbor who is cleaning out a boat shop as part of an estate liquidation. It looks like it could be a decent restoration project.

So far some of the mechanisms have moved with some coaxing, with the exception of the elevating slide and the clapper box, which seem to be stuck tight. I envision the possibility of a thorough cleaning of the ways and mechanisms and possibly repainting. Any thoughts on a historically accurate color? Under the peeling grey layer it would seem to be a dull black.

It has a 110v motor belt driving what appears to be a small 4 speed transmission that chain drives the primary jackshaft (my knowledge of nomenclature is sorely lacking so bear with me). I assume this to be a later addition to what was originally a lineshaft driven tool.

I found a reference to G & E's company history at: Ezra Gould; Gould Machine Co. - History | VintageMachinery.org

According to which, the company went by the "E. Gould & Eberhardt" name circa 1877-1883. Would it be reasonable to consider this shaper to be that old?

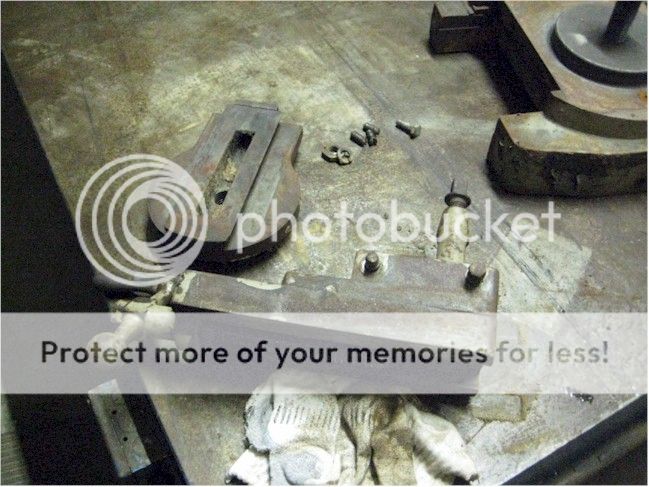

I have already begun to dismantle the swivel head and vice. I will post additional pictures of the disassembly as I can get them processed.

It was discovered by a neighbor who is cleaning out a boat shop as part of an estate liquidation. It looks like it could be a decent restoration project.

So far some of the mechanisms have moved with some coaxing, with the exception of the elevating slide and the clapper box, which seem to be stuck tight. I envision the possibility of a thorough cleaning of the ways and mechanisms and possibly repainting. Any thoughts on a historically accurate color? Under the peeling grey layer it would seem to be a dull black.

It has a 110v motor belt driving what appears to be a small 4 speed transmission that chain drives the primary jackshaft (my knowledge of nomenclature is sorely lacking so bear with me). I assume this to be a later addition to what was originally a lineshaft driven tool.

I found a reference to G & E's company history at: Ezra Gould; Gould Machine Co. - History | VintageMachinery.org

According to which, the company went by the "E. Gould & Eberhardt" name circa 1877-1883. Would it be reasonable to consider this shaper to be that old?

I have already begun to dismantle the swivel head and vice. I will post additional pictures of the disassembly as I can get them processed.

Last edited: