How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

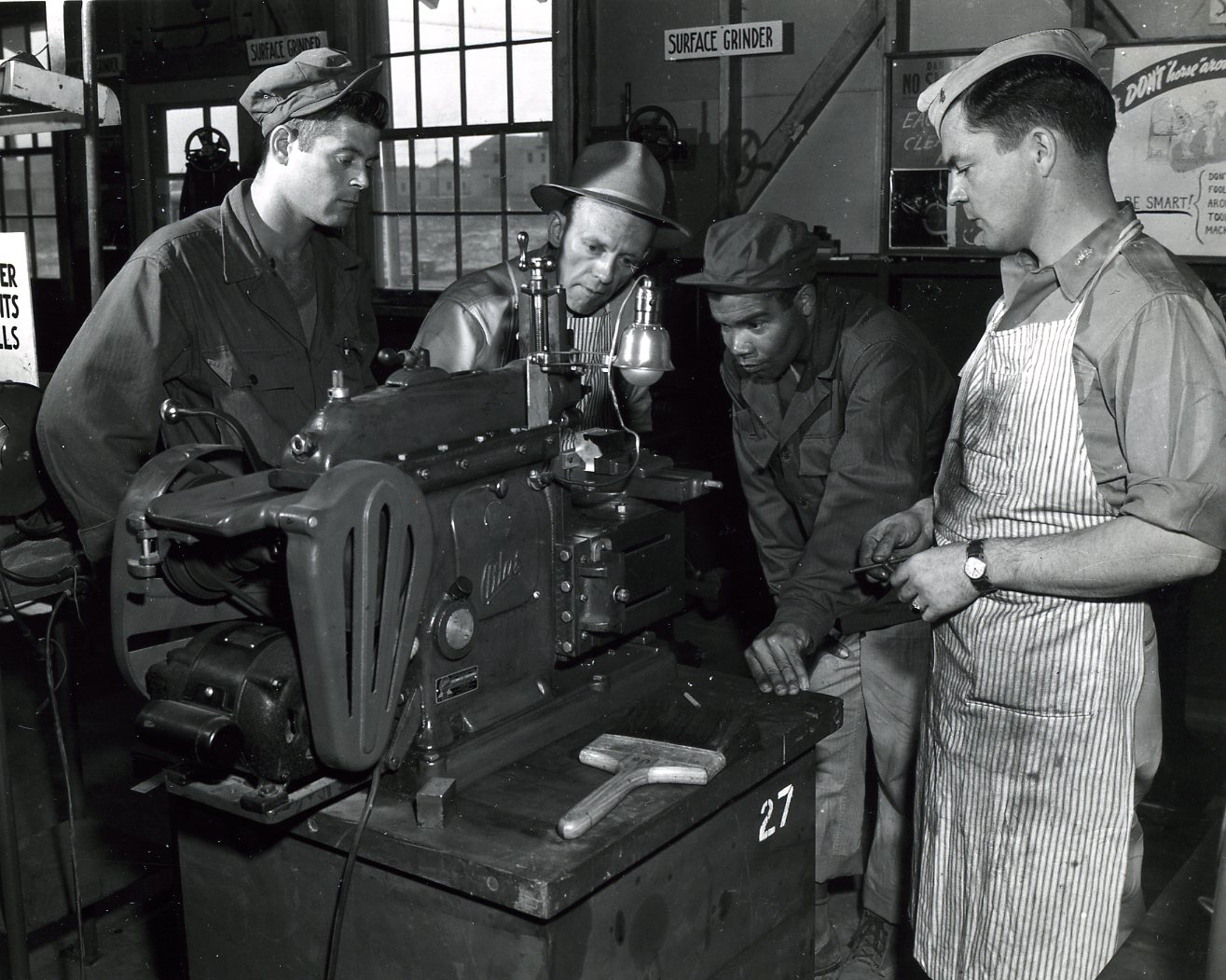

Photo: ...Wakeman General Hospital...Camp Atterbury...Indiana...

- Thread starter lathefan

- Start date

- Replies 19

- Views 6,354

Greg Menke

Diamond

- Joined

- Feb 22, 2004

- Location

- Baltimore, MD, USA

Love the "Protect Your Vision" poster on the wall & a shop full of guys w/ no glasses

SouthBendModel34

Diamond

- Joined

- Feb 4, 2004

- Location

- Metuchen, NJ, USA

Machine Identifications

The shaper clearly says Atlas on the side.

The fellow with two chevrons and a T on his arm is running a lathe that might also be an Atlas, but I would not say that I'm sure of it.

And, what rank IS that, anyway? I've heard of a "Technical Sargent" rank that wears THREE chevrons and a T. What is he? A "Technical Corporal?"

All these soldiers are presumably recovering from wounds or diseases acquired in service. It would have been appropriate to post this on Veteran's Day - in fact, I hope someone remembers to give this a "bump" on Nov. 11th.

John Ruth

The shaper clearly says Atlas on the side.

The fellow with two chevrons and a T on his arm is running a lathe that might also be an Atlas, but I would not say that I'm sure of it.

And, what rank IS that, anyway? I've heard of a "Technical Sargent" rank that wears THREE chevrons and a T. What is he? A "Technical Corporal?"

All these soldiers are presumably recovering from wounds or diseases acquired in service. It would have been appropriate to post this on Veteran's Day - in fact, I hope someone remembers to give this a "bump" on Nov. 11th.

John Ruth

manualmachinist

Stainless

- Joined

- Oct 5, 2012

- Location

- Battleground, Washington

You are correct, it is an Atlas.The shaper clearly says Atlas on the side.

The fellow with two chevrons and a T on his arm is running a lathe that might also be an Atlas, but I would not say that I'm sure of it.

And, what rank IS that, anyway? I've heard of a "Technical Sargent" rank that wears THREE chevrons and a T. What is he? A "Technical Corporal?"

All these soldiers are presumably recovering from wounds or diseases acquired in service. It would have been appropriate to post this on Veteran's Day - in fact, I hope someone remembers to give this a "bump" on Nov. 11th.

John Ruth

1. they had flat ways

2. there is an Atlas badge on the end of the bed...

randyc

Stainless

- Joined

- Aug 18, 2003

- Location

- Eureka, CA, USA

Leave it to the Army to post a "surface Grinder" sign over the surface grinder  Yeah, LOTS of Atlas machinery in that shop.

Yeah, LOTS of Atlas machinery in that shop.

If that's aluminum he's turning, he's asking for a nasty cut on his hand + with those stringy chips I wouldn't be wearing long sleeve shirt !

Yeah, LOTS of Atlas machinery in that shop.

Yeah, LOTS of Atlas machinery in that shop.If that's aluminum he's turning, he's asking for a nasty cut on his hand + with those stringy chips I wouldn't be wearing long sleeve shirt !

Joe Michaels

Diamond

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2004

- Location

- Shandaken, NY, USA

In the first picture, the fourth (rear-most) lathe is a "Roundhead" LeBlond Regal lathe. It is the lathe not being used in that photo.

The military was big on labelling everything and anything, no matter how obvious, and putting nameplates with operating instructions on most of their equipment.

Hanging a sign reading "surface grinder" is about right for the military in that era. Look at military vehicles from WWII and onward: they had the tire pressure stencilled on each fender, maximum speed painted on a lot of the vehicles, type of fuel stencilled on the tank, and on it went. Get into a naval vessel's engine room, and everything is labelled, and every pipe has the "service" ("main steam", "condensate", "fuel oil", lube oil", etc) painted on it or at least on the jacketing. Every valve is labelled as well. In civilian powerplants, this is also done. Some things are obvious, but the belief is labelling everything clearly prevents mistakes or missed communications.

In the pictures in this thread, the shop shown was part of the convalescent facilities attached to a military hospital. It was not a working machine shop, but a classroom. It may have been intended to give recovering soldiers a chance to do something aside from reading or playing cards and a sense of self-worth. It may have been intended to give recovering soldiers a chance to get an introduction to machine shop work with the thought being that they might go into that line of work once they were discharged into civilian life. Either way, it was a shop designed to introduce the recovering soldiers to machine work, and nothing was left to chance. Hence, numerous instructional charts, safety posters, and labelling to the point of stating the obvious. But, if a recovering soldier had never been in a machine shop, labelling the machine tools would help him and maybe spare him the embarassment of asking what might seem "the obvious" or otherwise "stupid" questions.

The military was big on labelling everything and anything, no matter how obvious, and putting nameplates with operating instructions on most of their equipment.

Hanging a sign reading "surface grinder" is about right for the military in that era. Look at military vehicles from WWII and onward: they had the tire pressure stencilled on each fender, maximum speed painted on a lot of the vehicles, type of fuel stencilled on the tank, and on it went. Get into a naval vessel's engine room, and everything is labelled, and every pipe has the "service" ("main steam", "condensate", "fuel oil", lube oil", etc) painted on it or at least on the jacketing. Every valve is labelled as well. In civilian powerplants, this is also done. Some things are obvious, but the belief is labelling everything clearly prevents mistakes or missed communications.

In the pictures in this thread, the shop shown was part of the convalescent facilities attached to a military hospital. It was not a working machine shop, but a classroom. It may have been intended to give recovering soldiers a chance to do something aside from reading or playing cards and a sense of self-worth. It may have been intended to give recovering soldiers a chance to get an introduction to machine shop work with the thought being that they might go into that line of work once they were discharged into civilian life. Either way, it was a shop designed to introduce the recovering soldiers to machine work, and nothing was left to chance. Hence, numerous instructional charts, safety posters, and labelling to the point of stating the obvious. But, if a recovering soldier had never been in a machine shop, labelling the machine tools would help him and maybe spare him the embarassment of asking what might seem "the obvious" or otherwise "stupid" questions.

kitno455

Titanium

- Joined

- Jul 9, 2010

- Location

- Virginia, USA

The other lathes in the first picture are South Bends.

allan

allan

Leave it to the Army to post a "surface Grinder" sign over the surface grinderYeah, LOTS of Atlas machinery in that shop.

If that's aluminum he's turning, he's asking for a nasty cut on his hand + with those stringy chips I wouldn't be wearing long sleeve shirt !

...looks to me like he is turning plastic...I added some links to enlarged views if you want a closer look...

jdleach

Stainless

- Joined

- Sep 19, 2009

- Location

- Columbus, IN USA

Camp Atterbury is about 15 miles just north of where I live here in Columbus, IN. Not sure about what all is left from the WWII period, but it is most likely all gone. It is a running military installation, and was ramped up after 9/11 to serve the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The associated Bakalar air base (Atterbury and Bakalar operated together, but were separate installations), located within the city limits at the north edge of town, was closed sometime in the 1970's and became the Columbus municipal airport. Little remains of the WWII infrastructure. The road and street system is still intact, and you can discern where the entrance guard shack once stood by the wide spot in the street. I think only 3 buildings remain. One is a rather neat looking old hanger (still in use), the beacon tower, and the base chapel. Several small machine shops, Flambeau molding (of yo-yo fame), the local IUPUC campus, a city fire station, local National Guard post,and some office buildings now populate the area. The redevelopment was done well, and tastefully. It still retains the feel of a military base, but also has a bit of a park-like appearance.

While it is rather sad that much more could not have been preserved, it is also understandable why. Bakalar was one of hundreds of small installations constructed rapidly during WWII to serve a specific purpose, and were never intended to be truly permanent. Almost all the buildings were either Quonset huts, or wooden shot-gun affairs. To look at photos taken during the war years, the buildings look little better than shacks. Time and use were not very kind to them. My understanding is that the lone shot-gun building left, the chapel, is pretty difficult to maintain.

The associated Bakalar air base (Atterbury and Bakalar operated together, but were separate installations), located within the city limits at the north edge of town, was closed sometime in the 1970's and became the Columbus municipal airport. Little remains of the WWII infrastructure. The road and street system is still intact, and you can discern where the entrance guard shack once stood by the wide spot in the street. I think only 3 buildings remain. One is a rather neat looking old hanger (still in use), the beacon tower, and the base chapel. Several small machine shops, Flambeau molding (of yo-yo fame), the local IUPUC campus, a city fire station, local National Guard post,and some office buildings now populate the area. The redevelopment was done well, and tastefully. It still retains the feel of a military base, but also has a bit of a park-like appearance.

While it is rather sad that much more could not have been preserved, it is also understandable why. Bakalar was one of hundreds of small installations constructed rapidly during WWII to serve a specific purpose, and were never intended to be truly permanent. Almost all the buildings were either Quonset huts, or wooden shot-gun affairs. To look at photos taken during the war years, the buildings look little better than shacks. Time and use were not very kind to them. My understanding is that the lone shot-gun building left, the chapel, is pretty difficult to maintain.

reggie_obe

Diamond

- Joined

- Jul 11, 2004

- Location

- Reddington, N.J., U.S.A.

...looks to me like he is turning plastic...I added some links to enlarged views if you want a closer look...

What plastics were in common use in this time period? Nylon, Bakelite, polyvinyl chloride and what else?

Seriously doubt that in the early days of the plastics industry, the military would have procured plastic in bar form for them to practice on. Given that some plastics are difficult to turn (even with proper tool geometry), Aluminum would be a more forgiving material for a "student" soldier to practice on.

Vladymere gr

Hot Rolled

- Joined

- Dec 10, 2008

- Location

- Charlotte, NC

Could this have been a shop for making prosthetics for soldiers missing limbs?

Vlad

Vlad

Ohio Mike

Titanium

- Joined

- Oct 30, 2008

- Location

- Central Ohio, USA

And, what rank IS that, anyway? I've heard of a "Technical Sargent" rank that wears THREE chevrons and a T. What is he? A "Technical Corporal?"

Ranks were different during the war they changed very early in 1942. That rank would be Technician Fifth Grade "T5" the equivalent to a corporal "E5". An early incarnation of what could become the Specialist grades a decade later.

I like their improvised chip pans under the lathes in picture #1. Pretty sure Camp Atterbury is a Indiana National Guard facility.

duckfarmer27

Stainless

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Location

- Upstate NY

Camp Atterbury does belong to the Indiana Army National Guard, and has had quite a few improvements since 9-11 as it has been used a lot for mobilizing reserve component units.

As to the old buildings - I can recall living in buildings that still looked like that into the 80s - and I started living in them the summer of 69. I'm going by memory, but I believe the buildings were designed for a life span of 5 years. Can't remember the number of the manual, but we had the 'big red books' (spent most of my Army career as a combat engineer) which were the prints (in a C size as I recall) for those buildings. Two volumes, and had a table in front. You want a place to house a 'whatever' - infantry division. Table told you go to print X for the proposed laydown - modify for terrain, of course. And then you build 10 of this, 5 of this, etc. That was the way they had to do it back then. I don't think the plans were ever used much after WWII but did hang around as 'usable' for a long time.

The pictures appear, to me, to have been a one story building converted to shop use - usually those were orderly rooms, supply buildings, etc. Note the pitched roof. If you look out the windows you can see two story barracks buildings. Heat and hot water were from separate coal fired devices that required tending - and were in the 'boiler room' at the end of the barracks. Summer of 69 I was living in one of those at Fort Indiantown Gap, PA. About our 3d day the 1940 cast iron water heater self destructed. Took them a day or two and they pronounced no solution except to put in a new oil fired hot water heater. As a result we were the only guys who actually had hot water. 40 of us lived in the barracks (20 upstairs, 20 downstairs, 5 bunk beds on each side of the aisle, by squad. Plus a couple cooks upstairs in the 'cooks room' and a grizzled SFC in the one cadre room on the first floor. Once word got out we had hot water it got interesting. Our rule was our platoon first, then if anyone else in the company (4 platoons) wanted, they could use our shower. We'd come in out of the field and there would be a line waiting to use the hot water. Mess halls had cast iron pot bellied stoves that got to be collector - and scrap value - items. Later on they were actually chained to the buildings

With no insulation at all in the buildings winter living could get interesting. I remember once in the early 80s at Fort Drum (Northern NY on Canadian border) the ice on the roof slid off and crushed a couple of cars. Luckily nobody hurt and after that no parking next to the building in the winter.

In the 90s the cost of maintaining, even for causal summer use by reserve component soldiers got to be too much. So they were bulldozed almost everywhere and no replacements put up in many cases.

I recall there used to be a part of one set up in the Smithsonian, but that was years ago.

Dale

As to the old buildings - I can recall living in buildings that still looked like that into the 80s - and I started living in them the summer of 69. I'm going by memory, but I believe the buildings were designed for a life span of 5 years. Can't remember the number of the manual, but we had the 'big red books' (spent most of my Army career as a combat engineer) which were the prints (in a C size as I recall) for those buildings. Two volumes, and had a table in front. You want a place to house a 'whatever' - infantry division. Table told you go to print X for the proposed laydown - modify for terrain, of course. And then you build 10 of this, 5 of this, etc. That was the way they had to do it back then. I don't think the plans were ever used much after WWII but did hang around as 'usable' for a long time.

The pictures appear, to me, to have been a one story building converted to shop use - usually those were orderly rooms, supply buildings, etc. Note the pitched roof. If you look out the windows you can see two story barracks buildings. Heat and hot water were from separate coal fired devices that required tending - and were in the 'boiler room' at the end of the barracks. Summer of 69 I was living in one of those at Fort Indiantown Gap, PA. About our 3d day the 1940 cast iron water heater self destructed. Took them a day or two and they pronounced no solution except to put in a new oil fired hot water heater. As a result we were the only guys who actually had hot water. 40 of us lived in the barracks (20 upstairs, 20 downstairs, 5 bunk beds on each side of the aisle, by squad. Plus a couple cooks upstairs in the 'cooks room' and a grizzled SFC in the one cadre room on the first floor. Once word got out we had hot water it got interesting. Our rule was our platoon first, then if anyone else in the company (4 platoons) wanted, they could use our shower. We'd come in out of the field and there would be a line waiting to use the hot water. Mess halls had cast iron pot bellied stoves that got to be collector - and scrap value - items. Later on they were actually chained to the buildings

With no insulation at all in the buildings winter living could get interesting. I remember once in the early 80s at Fort Drum (Northern NY on Canadian border) the ice on the roof slid off and crushed a couple of cars. Luckily nobody hurt and after that no parking next to the building in the winter.

In the 90s the cost of maintaining, even for causal summer use by reserve component soldiers got to be too much. So they were bulldozed almost everywhere and no replacements put up in many cases.

I recall there used to be a part of one set up in the Smithsonian, but that was years ago.

Dale

Ohio Mike

Titanium

- Joined

- Oct 30, 2008

- Location

- Central Ohio, USA

As to the old buildings - I can recall living in buildings that still looked like that into the 80s - and I started living in them the summer of 69. I'm going by memory, but I believe the buildings were designed for a life span of 5 years. Can't remember the number of the manual, but we had the 'big red books' (spent most of my Army career as a combat engineer) which were the prints (in a C size as I recall) for those buildings. Two volumes, and had a table in front. You want a place to house a 'whatever' - infantry division. Table told you go to print X for the proposed laydown - modify for terrain, of course. And then you build 10 of this, 5 of this, etc. That was the way they had to do it back then. I don't think the plans were ever used much after WWII but did hang around as 'usable' for a long time.

Today USACE would have a stack of prints two inches thick for a single little building. I recall seeing some prints for some war era warehouses. Entire building was a set of like maybe 6 sheets. End view, side view and then section wall, then maybe some detail shots of the foundation etc. If you needed a building 1500 ft long you just built the end wall with a section then repeated sections till you got to the length you needed and slapped on another end wall.

Joe Michaels

Diamond

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2004

- Location

- Shandaken, NY, USA

Duckfarmer:

My late father was a combat engineer during WWII. Kind of a crazy story. Dad started at Cornell Ag School in about 1935. Between not coming from a farming family, not having anyone to kind of guide him along, and the depression, Dad quit Cornell after 2 years. He got a good basic education in a lot of practical things. Coming home from Cornell, Dad took a job with his brother-in-law, a licensed plumber. Dad "put his time in" and by 1941 was a journeyman plumber. Somewhere during the time he was working for his brother in law, Dad had a bathtub get away from him while lugging it up some stairs on a job. It tore his rotator cuff. Dad had no money to get it fixed, so lived with it. When WWII broke out, Dad figured he'd be best off enlisting in the Seabees. At the physical exam, they took one look at Dad's torn rotator cuff and pronounced him unfit for military service. Dad got a draft notice some time after that, and reported to the infamous induction center on Whitehall Street in NYC. They took one look at his rotator cuff and also pronounced Dad unfit for military service. Dad felt a need to do his part and asked for a waiver. He got it. Dad was put into a combat engineer outfit, part of the Keystone Division (Pennsylvania). Most of the men in it were former coal miners and some farmers and members of the building trades rounded it out. Dad went through basic training and combat engineer training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., torn rotator cuff and all. Dad said he spent a lot of his time at Fort Leonard Wood putting plumbing into new barracks. His combat engineer outfit, aside from some rudimentary training in running heavy equipment and throwing up bridges, spent their time building barracks to handle the buildup for WWII. Dad said that even in wartime, the barracks were piped with screwed brass water piping, and cast iron soil pipe with "Calked and run" joints. Of course, in 1942, PVC and sweated copper pipe were unknown. Dad knew how to run pipe and how to do lead work, and he kept plenty busy. He said it beat a lot of what the rest of the crowd was doing. dad did say that they got up at some early hour, before dawn, have breakfast, and would run a few miles carrying their service rifles. After breakfast, if they were not scheduled for training, they were detailed to work on building more barracks.

Dad told the story of two Greek immigrants in his outfit. They were carpenters in civilian life. One morning, they put their tools down after a couple of hours. The sergeant started hollering at them. the Greek carpenters had minimal English between them. One said something to the sergeant like "no pay, no work, Army pay for 2 hours work." According to Dad, the Greeks had figured out what the Army pay equated to based on the hourly rate they got in civilian life. The sergeant yelled and cussed, and threatened to put the Greeks on KP. Some which way, the Greeks were gotten to understand that KP meant working in the kitchen. After some palaver in Greek, one of them said: "OK, we go on KP. Cousin in New York start in kitchen, owns restaurants." Dad said the sergeant threw his hands up and left them.

The other story Dad told me concerned a couple of boilermakers and a new commanding officer. The boilermakers were from Texas. No one could figure out what to assign them to. The outfit had no cooks. The boilermakers said they'd cook. They went to the commissary and drew the usual supplies: chipped beef, rice, and dried beans. Somewhere the boilermakers got hold of the spices to make chili. They made the chipped beef and beans into chile con carne and served it over the rice. Dad said everyone ate it and liked it. The boilermakers kept on cooking. Soon enough, a new commanding officer was assigned, fresh out of OCS. Dad said the new commanding officer had been a letter carrier in his civilian life and had some political pull to get himself into OCS. Dad also said the guys in his outfit were a tight bunch. They were all either Pennsylvania coal miners, or members of the building trades with a few mechanics and farmers thrown in. Dad said they did not trust anyone who was not from that type of background. The officer assigned to them was not from that type of background, and let it be known he intended to finish the war as a full bird colonel. Dad said the men in his outfit included a few retreads from WWI, and they got together and talked it over. They figured as an engineer outfit, they'd already be out in front and in harm's way without having to look for more trouble. An officer intent on making a name for himself and fresh out of OCS and not a member of the building trades or a coal miner was not to be trusted. The new officer was also a "book man". Before too long, he discovered the men in his outfit were eating chili con carne instead of creamed chipped beef on toast (known as s--t on a shingle). The officer immediately requisitioned a couple of "Army cooks" and put the boilermakers on some other detail. That was the end of any good food. It was also the end of that officer.

Dad said the men got together and decided that officer was going to get them all killed as he was not particularly bright, wanted to make a name for himself, and was a book man. The stopping of the cooking of chili was the last straw. Dad said that officer never left Fort Leonard Wood alive, and as Dad put it, "it was no accident". Dad said the combat engineers in his outfit were a tight bunch, and that officer did not fit in nor did he inspire trust or respect.

Dad taught me to cook a mean pot of chili when I was a kid. We'd eat it with chopped raw onions on top, plenty hot, and Dad would give me some of his beer. It was one Sunday night that he told me about the boilermakers and the chili. Years later, when I was in college, I asked about joining ROTC, and made my case as to how there was an Engineer ROTC company at college. Before I finished asking, Dad hollered out that I was crazy and knocked me down with one quick left. I got up from the floor, wondering what day of the week it was. Dad was hollering about the most useless thing on earth being an ROTC second lieutenant in an Engineer Outfit. Dad had a short fuse for certain things, and I'd found one of those things. While his right arm was messed up from the injury to the rotator cuff and then being wounded, dad's left arm more than made up for it. Dad told me the life expectancy of freshly made Engineer 2nd Lieutenants in WWII was measured in minutes, and many were shot in the back by their own men. Dad said no son of his was going to be an ROTC officer, got me a drink, and told me about the officer he'd had at Fort Leonard Wood who made the fatal mistake of stopping the men from doing their own cooking. Dad spat that officer's name out like he was spitting out a wad of phlegm, and said men like that had no place leading other men, let alone in an engineer outfit.

Dad finished his combat engineer training, and said he was rushed through such things as learning to blow up bridges and infrastructure, learning to run heavy equipment and drive heavy trucks, and how to build various things to stop an enemy advance. Mom had gone out to Fort Leonard Wood to see Dad graduate from engineer school. They returned east on a train which, according to both Mom and Dad, was made up of "Civil War" passenger coaches. Doorways had been cut in the end bulkheads of a steel boxcar, and a sand-filled box with a fire was used for cooking. Everyone walked through from one passenger coach into that boxcar to get their meals, then out the other end to sit down in the remaining coaches to eat. Dad reported to Fort Devon, in Massachusetts, which was the staging area for embarkation to England. By now, Dad's rotator cuff was in really bad condition. Army physicians examined Dad and offered him a medical discharge. Dad asked to stay in and wanted to help in the fight. So, a "retread" (WWI vet) surgeon operated on Dad's shoulder at Fort Devon. As they told Dad, he'd have an ocean voyage to recuperate. Dad went over to England on a converted banana boat. Another GI carried Dad's duffle up the gangplank since Dad could not do it himself. Dad arrived in England was put on light duty. They made Dad the company clerk. Dad, while articulate and literate, had to type by hunt and peck with two fingers, and was dyslectic in the bargain. Leave it to the Army.

Dad went ashore on the 2nd wave of D Day. He fought through Europe, was wounded a couple of times and shipped home on a stretcher. I have Dad's WWII "Soldier's Handbook", along with "Unarmed Defense for the American Soldier" (which Dad handed me when I was getting beat up by bullies in grade school), and Dad's combat engineer manuals on my shelves. I also have the booklet with Dad's qualification records on the M1 Garand Rifle, M1903A3 Springfield, and M1911 pistol, all at Fort Leonard Wood.

WWII era military "architecture" is recognizeable. Sometimes, driving along, we might see some clap-board sided housing, all laid out in orderly rows, all uniform in design. It has a certain look to it, and there is no mistaking what was once a military installation.

My late father was a combat engineer during WWII. Kind of a crazy story. Dad started at Cornell Ag School in about 1935. Between not coming from a farming family, not having anyone to kind of guide him along, and the depression, Dad quit Cornell after 2 years. He got a good basic education in a lot of practical things. Coming home from Cornell, Dad took a job with his brother-in-law, a licensed plumber. Dad "put his time in" and by 1941 was a journeyman plumber. Somewhere during the time he was working for his brother in law, Dad had a bathtub get away from him while lugging it up some stairs on a job. It tore his rotator cuff. Dad had no money to get it fixed, so lived with it. When WWII broke out, Dad figured he'd be best off enlisting in the Seabees. At the physical exam, they took one look at Dad's torn rotator cuff and pronounced him unfit for military service. Dad got a draft notice some time after that, and reported to the infamous induction center on Whitehall Street in NYC. They took one look at his rotator cuff and also pronounced Dad unfit for military service. Dad felt a need to do his part and asked for a waiver. He got it. Dad was put into a combat engineer outfit, part of the Keystone Division (Pennsylvania). Most of the men in it were former coal miners and some farmers and members of the building trades rounded it out. Dad went through basic training and combat engineer training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., torn rotator cuff and all. Dad said he spent a lot of his time at Fort Leonard Wood putting plumbing into new barracks. His combat engineer outfit, aside from some rudimentary training in running heavy equipment and throwing up bridges, spent their time building barracks to handle the buildup for WWII. Dad said that even in wartime, the barracks were piped with screwed brass water piping, and cast iron soil pipe with "Calked and run" joints. Of course, in 1942, PVC and sweated copper pipe were unknown. Dad knew how to run pipe and how to do lead work, and he kept plenty busy. He said it beat a lot of what the rest of the crowd was doing. dad did say that they got up at some early hour, before dawn, have breakfast, and would run a few miles carrying their service rifles. After breakfast, if they were not scheduled for training, they were detailed to work on building more barracks.

Dad told the story of two Greek immigrants in his outfit. They were carpenters in civilian life. One morning, they put their tools down after a couple of hours. The sergeant started hollering at them. the Greek carpenters had minimal English between them. One said something to the sergeant like "no pay, no work, Army pay for 2 hours work." According to Dad, the Greeks had figured out what the Army pay equated to based on the hourly rate they got in civilian life. The sergeant yelled and cussed, and threatened to put the Greeks on KP. Some which way, the Greeks were gotten to understand that KP meant working in the kitchen. After some palaver in Greek, one of them said: "OK, we go on KP. Cousin in New York start in kitchen, owns restaurants." Dad said the sergeant threw his hands up and left them.

The other story Dad told me concerned a couple of boilermakers and a new commanding officer. The boilermakers were from Texas. No one could figure out what to assign them to. The outfit had no cooks. The boilermakers said they'd cook. They went to the commissary and drew the usual supplies: chipped beef, rice, and dried beans. Somewhere the boilermakers got hold of the spices to make chili. They made the chipped beef and beans into chile con carne and served it over the rice. Dad said everyone ate it and liked it. The boilermakers kept on cooking. Soon enough, a new commanding officer was assigned, fresh out of OCS. Dad said the new commanding officer had been a letter carrier in his civilian life and had some political pull to get himself into OCS. Dad also said the guys in his outfit were a tight bunch. They were all either Pennsylvania coal miners, or members of the building trades with a few mechanics and farmers thrown in. Dad said they did not trust anyone who was not from that type of background. The officer assigned to them was not from that type of background, and let it be known he intended to finish the war as a full bird colonel. Dad said the men in his outfit included a few retreads from WWI, and they got together and talked it over. They figured as an engineer outfit, they'd already be out in front and in harm's way without having to look for more trouble. An officer intent on making a name for himself and fresh out of OCS and not a member of the building trades or a coal miner was not to be trusted. The new officer was also a "book man". Before too long, he discovered the men in his outfit were eating chili con carne instead of creamed chipped beef on toast (known as s--t on a shingle). The officer immediately requisitioned a couple of "Army cooks" and put the boilermakers on some other detail. That was the end of any good food. It was also the end of that officer.

Dad said the men got together and decided that officer was going to get them all killed as he was not particularly bright, wanted to make a name for himself, and was a book man. The stopping of the cooking of chili was the last straw. Dad said that officer never left Fort Leonard Wood alive, and as Dad put it, "it was no accident". Dad said the combat engineers in his outfit were a tight bunch, and that officer did not fit in nor did he inspire trust or respect.

Dad taught me to cook a mean pot of chili when I was a kid. We'd eat it with chopped raw onions on top, plenty hot, and Dad would give me some of his beer. It was one Sunday night that he told me about the boilermakers and the chili. Years later, when I was in college, I asked about joining ROTC, and made my case as to how there was an Engineer ROTC company at college. Before I finished asking, Dad hollered out that I was crazy and knocked me down with one quick left. I got up from the floor, wondering what day of the week it was. Dad was hollering about the most useless thing on earth being an ROTC second lieutenant in an Engineer Outfit. Dad had a short fuse for certain things, and I'd found one of those things. While his right arm was messed up from the injury to the rotator cuff and then being wounded, dad's left arm more than made up for it. Dad told me the life expectancy of freshly made Engineer 2nd Lieutenants in WWII was measured in minutes, and many were shot in the back by their own men. Dad said no son of his was going to be an ROTC officer, got me a drink, and told me about the officer he'd had at Fort Leonard Wood who made the fatal mistake of stopping the men from doing their own cooking. Dad spat that officer's name out like he was spitting out a wad of phlegm, and said men like that had no place leading other men, let alone in an engineer outfit.

Dad finished his combat engineer training, and said he was rushed through such things as learning to blow up bridges and infrastructure, learning to run heavy equipment and drive heavy trucks, and how to build various things to stop an enemy advance. Mom had gone out to Fort Leonard Wood to see Dad graduate from engineer school. They returned east on a train which, according to both Mom and Dad, was made up of "Civil War" passenger coaches. Doorways had been cut in the end bulkheads of a steel boxcar, and a sand-filled box with a fire was used for cooking. Everyone walked through from one passenger coach into that boxcar to get their meals, then out the other end to sit down in the remaining coaches to eat. Dad reported to Fort Devon, in Massachusetts, which was the staging area for embarkation to England. By now, Dad's rotator cuff was in really bad condition. Army physicians examined Dad and offered him a medical discharge. Dad asked to stay in and wanted to help in the fight. So, a "retread" (WWI vet) surgeon operated on Dad's shoulder at Fort Devon. As they told Dad, he'd have an ocean voyage to recuperate. Dad went over to England on a converted banana boat. Another GI carried Dad's duffle up the gangplank since Dad could not do it himself. Dad arrived in England was put on light duty. They made Dad the company clerk. Dad, while articulate and literate, had to type by hunt and peck with two fingers, and was dyslectic in the bargain. Leave it to the Army.

Dad went ashore on the 2nd wave of D Day. He fought through Europe, was wounded a couple of times and shipped home on a stretcher. I have Dad's WWII "Soldier's Handbook", along with "Unarmed Defense for the American Soldier" (which Dad handed me when I was getting beat up by bullies in grade school), and Dad's combat engineer manuals on my shelves. I also have the booklet with Dad's qualification records on the M1 Garand Rifle, M1903A3 Springfield, and M1911 pistol, all at Fort Leonard Wood.

WWII era military "architecture" is recognizeable. Sometimes, driving along, we might see some clap-board sided housing, all laid out in orderly rows, all uniform in design. It has a certain look to it, and there is no mistaking what was once a military installation.

jdleach

Stainless

- Joined

- Sep 19, 2009

- Location

- Columbus, IN USA

A couple of interesting points concerning these photos. I surmise that the shots were only marginally staged. I suspect the fellows in the photos are indeed convalescents, recovering from injury or disease. In the first photo, note the right arm of the first chap running the S.B. lathe. There is evidence of some type of scarring.

The young man in the second picture, while exhibiting no obvious wounds, is certainly dressed like an inmate at a recovery facility. The thing that struck me, was the lack of him wearing a belt. Outside of a military hospital, that would be a big no-no. I recall a short stint at Portsmouth Naval Hospital for surgery in 1979. While in residence, military protocol was almost non-existent, as the focus was on getting you well. After discharge though, it was back to the grind.

The last photo is probably the most "staged". But not by much. The dirty aprons, stained hands of the young officer, and casual dress of the enlisted guys speak of their being residents. The older gent in the fedora is probably a civilian supervisor/instructor.

The young man in the second picture, while exhibiting no obvious wounds, is certainly dressed like an inmate at a recovery facility. The thing that struck me, was the lack of him wearing a belt. Outside of a military hospital, that would be a big no-no. I recall a short stint at Portsmouth Naval Hospital for surgery in 1979. While in residence, military protocol was almost non-existent, as the focus was on getting you well. After discharge though, it was back to the grind.

The last photo is probably the most "staged". But not by much. The dirty aprons, stained hands of the young officer, and casual dress of the enlisted guys speak of their being residents. The older gent in the fedora is probably a civilian supervisor/instructor.

duckfarmer27

Stainless

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Location

- Upstate NY

Joe -

Hate to disagree with your Dad - but I think you would have made a fine engineer officer as you have the right attitude. That's basically the job you had at the power plant. It's all about taking care of the troops and doing the mission - but in a different place and time. And you learned a lot of that from your Dad.

Your Dad's medical situation reminds me of my wife's oldest brother. He graduated from high school in 1948, same year my wife was born. He went to Penn State and joined ROTC. At the end of your second year you have to pass a physical for the past two years - during which, back then (and as I did) you got the princely sum of $50 per month. When he got to the physical they did the usual cover one eye and read the chart. He did that OK, but then cover the other eye - well, he can't see anything other than light and dark out of that eye due to a problem during delivery when he was born. You'd never know it to look at him. So they throw him out of ROTC. He graduates and gets a teaching job just West of here. By then the Korean War is going and he gets a notice from the draft board to go to Scranton for a physical. Goes into the physical and at the eye exam says he can't see out of his one eye. Doc says, yeah right - your're 1A. So he gets drafted and sent to Fort Leonard Wood (or as many of us affectionately call it, Fort Lost in the Woods). Same thing there. He gets done with basic and AIT (Advanced Individual Training) as a combat engineer. They pull him in and say - hey, you are a college graduate and have done well, how about OCS? So Bill signs up for OCS and off to Fort Belvoir he goes (until the 80s enlisted engineer training was at Wood and offciers at Belvoir, now all at Wood). A week before OCS graduation he had to have a pre commissioning physical - doc says holy crap you're blind in one eye. He calmly tells the doc that is what he's been telling the Army for the past year and nobody would listen. So the CO calls him in - says its a Catch 22 - you can't get commissioned but we can't let you out of the Army because you're in so we'll keep you in as a private. Bill raises cain with them (it takes a lot to get him going, one of the calmest people I know) as he is at the top of his class and by this time the day or so before graduation. They finally relent, commission him but tell him they can't send him to Korea and a war zone because he should not even be in the Army. So he spends 3 years in Germany, coming out a captain and company commander of a combat engineer company. And with my time in I could tell more stories - believe the unbelievable.

When I was in training, before getting commissioned, I have to admit at times I shook my head at some of the future officers and later at some of my peers. The vast majority were good guys (I started in the days with no women) who did their level best. A few were like the idiot your Dad got saddled with. One thing you have to learn early - no way you can ever bluff or bullshit an American soldier. They spot a phony a mile away - and if they have to, take care of him. I was extremely lucky, as in my career there were 2 particular commanders I served under who were the most outstanding leaders I ever saw - fair, demanded the troops be cared for and worked our butts off - demanding more from the leaders than the soldiers. I learned a lot from them. My first unit at Fort Hood I had a Chief Warrant Officer who supposedly worked for me - when I should have been working for him. I was smart enough to learn from him - got more practical leadership training from him in 6 months than years of college, etc. Matter of fact the reason I'm the Duckfarmer is because, as Tito always said, 'You and me are just 2 dumb duckfarmers trying to get this straightened out' - whatever the mess was we were in. I'm still proud to be a duckfarmer trained by him and hope he approved of what I did in the next 32 plus years wearing a uniform. He's one of the reasons did as well as I did, in addition to all the great people I was fortunate enough to have working for me.

Dale

Hate to disagree with your Dad - but I think you would have made a fine engineer officer as you have the right attitude. That's basically the job you had at the power plant. It's all about taking care of the troops and doing the mission - but in a different place and time. And you learned a lot of that from your Dad.

Your Dad's medical situation reminds me of my wife's oldest brother. He graduated from high school in 1948, same year my wife was born. He went to Penn State and joined ROTC. At the end of your second year you have to pass a physical for the past two years - during which, back then (and as I did) you got the princely sum of $50 per month. When he got to the physical they did the usual cover one eye and read the chart. He did that OK, but then cover the other eye - well, he can't see anything other than light and dark out of that eye due to a problem during delivery when he was born. You'd never know it to look at him. So they throw him out of ROTC. He graduates and gets a teaching job just West of here. By then the Korean War is going and he gets a notice from the draft board to go to Scranton for a physical. Goes into the physical and at the eye exam says he can't see out of his one eye. Doc says, yeah right - your're 1A. So he gets drafted and sent to Fort Leonard Wood (or as many of us affectionately call it, Fort Lost in the Woods). Same thing there. He gets done with basic and AIT (Advanced Individual Training) as a combat engineer. They pull him in and say - hey, you are a college graduate and have done well, how about OCS? So Bill signs up for OCS and off to Fort Belvoir he goes (until the 80s enlisted engineer training was at Wood and offciers at Belvoir, now all at Wood). A week before OCS graduation he had to have a pre commissioning physical - doc says holy crap you're blind in one eye. He calmly tells the doc that is what he's been telling the Army for the past year and nobody would listen. So the CO calls him in - says its a Catch 22 - you can't get commissioned but we can't let you out of the Army because you're in so we'll keep you in as a private. Bill raises cain with them (it takes a lot to get him going, one of the calmest people I know) as he is at the top of his class and by this time the day or so before graduation. They finally relent, commission him but tell him they can't send him to Korea and a war zone because he should not even be in the Army. So he spends 3 years in Germany, coming out a captain and company commander of a combat engineer company. And with my time in I could tell more stories - believe the unbelievable.

When I was in training, before getting commissioned, I have to admit at times I shook my head at some of the future officers and later at some of my peers. The vast majority were good guys (I started in the days with no women) who did their level best. A few were like the idiot your Dad got saddled with. One thing you have to learn early - no way you can ever bluff or bullshit an American soldier. They spot a phony a mile away - and if they have to, take care of him. I was extremely lucky, as in my career there were 2 particular commanders I served under who were the most outstanding leaders I ever saw - fair, demanded the troops be cared for and worked our butts off - demanding more from the leaders than the soldiers. I learned a lot from them. My first unit at Fort Hood I had a Chief Warrant Officer who supposedly worked for me - when I should have been working for him. I was smart enough to learn from him - got more practical leadership training from him in 6 months than years of college, etc. Matter of fact the reason I'm the Duckfarmer is because, as Tito always said, 'You and me are just 2 dumb duckfarmers trying to get this straightened out' - whatever the mess was we were in. I'm still proud to be a duckfarmer trained by him and hope he approved of what I did in the next 32 plus years wearing a uniform. He's one of the reasons did as well as I did, in addition to all the great people I was fortunate enough to have working for me.

Dale

Joe Michaels

Diamond

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2004

- Location

- Shandaken, NY, USA

Duckfarmer:

Thanks for the kind words. I am sure the majority of officers are right-thinking, and good leaders. Dad, as you say, got saddled with something less than that.

I appreciate your thinking I would have made a good combat engineer officer. In truth, after rethinking the ROTC idea, and seeing the kinds of gung-ho individuals in ROTC at college, I abandoned any further thinking in that direction.

I was not making anything like good grades in my freshman year. Vietnam was going full blast, and if you did not have at least a C average, you were draft eligible. How the draft boards, in the pre-computer days, were going to keep track of every college student with a 2-S (student) deferment is something I never found out. I was on academic probation. Less than a C average. I was pretty gullible, and figured I was as good as IA. So, I walked over to the recruiting offices near the engineering school and went to see the Navy recruiter. As luck would have it, there was an old CPO in the office, hashmarks (for hitches served) down his sleeve. He asked me what I wanted. I said I wanted to enlist in the US Navy. I was an engineering school nerd, and probably something of a wimp at the time. The old CPO looked me up and down and asked me what I was doing with my life and why I wanted to enlist. I came clean, telling him I was a mechanical engineering student on academic probation, that I loved machinery and ships, and figured I'd best serve the USA in a US Navy ship's engine room. The old CPO took it all in, and said: "Son, this is no time for a kid like you to be enlisting. You are more service to the USA, yourself and your parents as a mechanical engineer. Go back to 'Poly and give it another try. If you were my own son, I'd be telling him the same thing. If things do not work out for you at 'Poly, come back and we'll sign you up. Now get out of here before the Officer returns, 'cause he WILL sign you up. Go home to your parents and talk it over." The old chief shook my hand and I went home. I thought some more about it, and realized the old chief was right. So, I studied, my grades got a little better, I discovered by taking Civil Engineering courses, I found a type of engineering I could handle quite easily and make A's and B's. So, I wound up with an undeclared minor in Civil, and a bachelor's in Mechanical Engineering.

As for the military, by my sophomore year, they had the draft lottery. My birthday came up as number 113. My grades were kind of yo-yoing, and I figured maybe it was the time to give the Navy a try. So, I dropped my deferment and went I-A. I figured if I got called, I'd go enlist in the Navy. Instead, my draft board called everyone with lottery numbers to 110. I was off the hook, and got some other draft classification which meant if there were another national emergency or draft, I would be eligible.

That was my experience with the military. Try to enlist and an old chief talks me out of it and sends me home. As time passed, I came to realize it is the people like that old chief who often keep the military functioning. Learning to lead is another matter, and some people, despite all manner of training and being promoted into positions which require leadership skills, never get it. Whether in the military or in industry, a lot is the same. Some people will "lead"- if you can call it that- by using title/position or the implied threat of some form of punishment (s--t work assignments, letter in a person's file which might block a promotion, etc). Some people "lead by default"- lay back, avoid decisions (and possibly taking some shred of responsibility) and letting things sort themselves out. Usually, this means the crew and some other people have to make decisions that could get them hanged, and then get the job done. Of course, if the job goes well, the boss- who has been wishy-washy at best, and more likely useless- suddenly claims the credit. If the job goes to s--t, the boss claims he never gave the orders for it to be done in the manner that resulted in things going to s--t, and hangs his chief mechanic or the whole crew out to dry for his own inaction. Seen plenty of that. Then, there are the bosses who lead by example, and admit their own shortcomings and never BS the crew if they have made a mistake. These bosses are the quietest leaders. They walk into a room or onto a job, and if they have been with their crew for some time previous, it is almost like an unspoken thing, the crew and the boss move as one mind and one body. To lead like that, a boss has to have paid his dues and shown he will never put a man into a situation he would not get into himself. He also has to know the work, and know his men, and he has to have his men's back. A lot of bosses will never do any of this, and think with a promotion and some management and leadership skills training, they are golden. Upper management will fall for the "drug of the week" and hire some hotshot management consultants and put on all kinds of training for new supervisors and similar. It is BS. Unless a man has a good grasp of the work and how the workplace operates, and unless he is always ready to take the point for his crew, no amount of training or seminars or promotions or degrees or titles will make a leader out of him. Seen it all too many times. I've seen all extremes, leading by fear and intimidation, leading by pulling rank, "leading" by doing nothing and taking no responsibility, and leading by respect.

Back when I was in college and thinking in terms of enlisting in the Navy, I figured my place was in a ship's engine room, and I hoped I'd be able to work up to being a Chief Petty Officer. I figured they were the USN equivalent of the old machinist foremen I looked up to. The cards played out differently, and I often thought of my job at the powerplant as a close equivalent to either a merchant marine chief engineer, or a CPO. It was a job that I called "a good berth", and the relationship with the crews was such that I stayed on nearly two years after I first became retirement eligible.

Thanks for the kind words. I am sure the majority of officers are right-thinking, and good leaders. Dad, as you say, got saddled with something less than that.

I appreciate your thinking I would have made a good combat engineer officer. In truth, after rethinking the ROTC idea, and seeing the kinds of gung-ho individuals in ROTC at college, I abandoned any further thinking in that direction.

I was not making anything like good grades in my freshman year. Vietnam was going full blast, and if you did not have at least a C average, you were draft eligible. How the draft boards, in the pre-computer days, were going to keep track of every college student with a 2-S (student) deferment is something I never found out. I was on academic probation. Less than a C average. I was pretty gullible, and figured I was as good as IA. So, I walked over to the recruiting offices near the engineering school and went to see the Navy recruiter. As luck would have it, there was an old CPO in the office, hashmarks (for hitches served) down his sleeve. He asked me what I wanted. I said I wanted to enlist in the US Navy. I was an engineering school nerd, and probably something of a wimp at the time. The old CPO looked me up and down and asked me what I was doing with my life and why I wanted to enlist. I came clean, telling him I was a mechanical engineering student on academic probation, that I loved machinery and ships, and figured I'd best serve the USA in a US Navy ship's engine room. The old CPO took it all in, and said: "Son, this is no time for a kid like you to be enlisting. You are more service to the USA, yourself and your parents as a mechanical engineer. Go back to 'Poly and give it another try. If you were my own son, I'd be telling him the same thing. If things do not work out for you at 'Poly, come back and we'll sign you up. Now get out of here before the Officer returns, 'cause he WILL sign you up. Go home to your parents and talk it over." The old chief shook my hand and I went home. I thought some more about it, and realized the old chief was right. So, I studied, my grades got a little better, I discovered by taking Civil Engineering courses, I found a type of engineering I could handle quite easily and make A's and B's. So, I wound up with an undeclared minor in Civil, and a bachelor's in Mechanical Engineering.

As for the military, by my sophomore year, they had the draft lottery. My birthday came up as number 113. My grades were kind of yo-yoing, and I figured maybe it was the time to give the Navy a try. So, I dropped my deferment and went I-A. I figured if I got called, I'd go enlist in the Navy. Instead, my draft board called everyone with lottery numbers to 110. I was off the hook, and got some other draft classification which meant if there were another national emergency or draft, I would be eligible.

That was my experience with the military. Try to enlist and an old chief talks me out of it and sends me home. As time passed, I came to realize it is the people like that old chief who often keep the military functioning. Learning to lead is another matter, and some people, despite all manner of training and being promoted into positions which require leadership skills, never get it. Whether in the military or in industry, a lot is the same. Some people will "lead"- if you can call it that- by using title/position or the implied threat of some form of punishment (s--t work assignments, letter in a person's file which might block a promotion, etc). Some people "lead by default"- lay back, avoid decisions (and possibly taking some shred of responsibility) and letting things sort themselves out. Usually, this means the crew and some other people have to make decisions that could get them hanged, and then get the job done. Of course, if the job goes well, the boss- who has been wishy-washy at best, and more likely useless- suddenly claims the credit. If the job goes to s--t, the boss claims he never gave the orders for it to be done in the manner that resulted in things going to s--t, and hangs his chief mechanic or the whole crew out to dry for his own inaction. Seen plenty of that. Then, there are the bosses who lead by example, and admit their own shortcomings and never BS the crew if they have made a mistake. These bosses are the quietest leaders. They walk into a room or onto a job, and if they have been with their crew for some time previous, it is almost like an unspoken thing, the crew and the boss move as one mind and one body. To lead like that, a boss has to have paid his dues and shown he will never put a man into a situation he would not get into himself. He also has to know the work, and know his men, and he has to have his men's back. A lot of bosses will never do any of this, and think with a promotion and some management and leadership skills training, they are golden. Upper management will fall for the "drug of the week" and hire some hotshot management consultants and put on all kinds of training for new supervisors and similar. It is BS. Unless a man has a good grasp of the work and how the workplace operates, and unless he is always ready to take the point for his crew, no amount of training or seminars or promotions or degrees or titles will make a leader out of him. Seen it all too many times. I've seen all extremes, leading by fear and intimidation, leading by pulling rank, "leading" by doing nothing and taking no responsibility, and leading by respect.

Back when I was in college and thinking in terms of enlisting in the Navy, I figured my place was in a ship's engine room, and I hoped I'd be able to work up to being a Chief Petty Officer. I figured they were the USN equivalent of the old machinist foremen I looked up to. The cards played out differently, and I often thought of my job at the powerplant as a close equivalent to either a merchant marine chief engineer, or a CPO. It was a job that I called "a good berth", and the relationship with the crews was such that I stayed on nearly two years after I first became retirement eligible.

duckfarmer27

Stainless

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2005

- Location

- Upstate NY

Joe -

I like that story - and your comments. Yep, leadership is leadership and you described the types for sure. I always said to be the manager or leader (and there is a difference) you had to be competent but not necessarily the best engineer or whatever. Competent technically but able to do the people end of things. We all don't have the same mix of talent - trick is to find the right spot for everyone. There usually is one, but sometimes its hard to find.

You were lucky and hit a good recruiter who must have also been a good non commissioned officer - I can tell by just that story. Reminds me of what my son did back in 1990. He had graduated from high school in June. Saddam invaded Kuwait the first of August. At the time I was a battalion commander of a combat engineer outfit - National Guard. In a story too long to tell we were in the first call up but never went - I spent about 6 weeks on active duty with some of my guys at the edge of the mobilization cliff trying to get things ready. My son was set to go to college but had talked to a recruiter towards the end of the school year as he thought he might like to try getting into flying helicopters. I was telling him to go get his education first and then he would have more options. Anyway, things start up and he mentions this again and I tell him whatever happens he can go to school first and anyway this thing will not last long enough anyway. About this time the recruiter calls him back. Tells him the draft will be sure to start up soon and if he enlists now he can get him going towards warrant officer flight school, if he waits he'll get drafted and not have a choice, etc. Plus plays on the country needs you line. So he calls me - I'm working at the armory - and tells me the story. Now in my position I have to worry about recruiting guys - one thing I beat into anyone who worked for me was to never lie, etc. And I think the recruiters I worked with were pretty straight shooters for the most part. But this was an active duty recruiter. I look up in the phone book and guess that the guy talking to my son works for the guy where I am (nearest big town). So I call in and ask to speak to the captain, only identifying myself as Dale so and so. The senior NCO on the phone says he can help me and I say, no I need to speak to the captain and leave the armory phone number. I had some great young guys who worked for me (who knew what was going on) - the captain calls in and asks for Dale and gets the reply 'please hold for the colonel' and slaps the phone on hold. Now I know I played dirty pool but wanted to set the stage. So I pick up and tell the captain my story - not loud, or anything else, just as a concerned parent, but very friendly. And as a fellow officer who has to recruit people I don't think either of us needs our people lying to potential soldiers. We had a good chat and he says he will look into it. Ten minutes later the phone rings - my son. He asks me what I did as he just got an apology call from the recruiter that he must have misunderstood, etc. etc. As I told my son there was probably a note next to his name to not bother calling again. Worst part of that six weeks was that when my wife took my son to college I could not go - my uncle pinch hit for me and drove them to the city.

You and I were, I think, in the same draft lottery - spring 1970 - as I think they did 2 years at once to start? Anyway, that was maybe a month before I was commissioned - I was signed, sealed and delivered to the US Army. I drew number 342 as I recall, my roommate was 350. We had a good laugh over that one.

I can't complain - like I said I was fortunate and had two great careers, one in the Army. Managed to do things and go places I never would have imagined. And I got to work with a lot of good people like that chief you ran into. And I was very blessed to have never had a class A accident or had to bury one of my soldiers.

Dale

I like that story - and your comments. Yep, leadership is leadership and you described the types for sure. I always said to be the manager or leader (and there is a difference) you had to be competent but not necessarily the best engineer or whatever. Competent technically but able to do the people end of things. We all don't have the same mix of talent - trick is to find the right spot for everyone. There usually is one, but sometimes its hard to find.

You were lucky and hit a good recruiter who must have also been a good non commissioned officer - I can tell by just that story. Reminds me of what my son did back in 1990. He had graduated from high school in June. Saddam invaded Kuwait the first of August. At the time I was a battalion commander of a combat engineer outfit - National Guard. In a story too long to tell we were in the first call up but never went - I spent about 6 weeks on active duty with some of my guys at the edge of the mobilization cliff trying to get things ready. My son was set to go to college but had talked to a recruiter towards the end of the school year as he thought he might like to try getting into flying helicopters. I was telling him to go get his education first and then he would have more options. Anyway, things start up and he mentions this again and I tell him whatever happens he can go to school first and anyway this thing will not last long enough anyway. About this time the recruiter calls him back. Tells him the draft will be sure to start up soon and if he enlists now he can get him going towards warrant officer flight school, if he waits he'll get drafted and not have a choice, etc. Plus plays on the country needs you line. So he calls me - I'm working at the armory - and tells me the story. Now in my position I have to worry about recruiting guys - one thing I beat into anyone who worked for me was to never lie, etc. And I think the recruiters I worked with were pretty straight shooters for the most part. But this was an active duty recruiter. I look up in the phone book and guess that the guy talking to my son works for the guy where I am (nearest big town). So I call in and ask to speak to the captain, only identifying myself as Dale so and so. The senior NCO on the phone says he can help me and I say, no I need to speak to the captain and leave the armory phone number. I had some great young guys who worked for me (who knew what was going on) - the captain calls in and asks for Dale and gets the reply 'please hold for the colonel' and slaps the phone on hold. Now I know I played dirty pool but wanted to set the stage. So I pick up and tell the captain my story - not loud, or anything else, just as a concerned parent, but very friendly. And as a fellow officer who has to recruit people I don't think either of us needs our people lying to potential soldiers. We had a good chat and he says he will look into it. Ten minutes later the phone rings - my son. He asks me what I did as he just got an apology call from the recruiter that he must have misunderstood, etc. etc. As I told my son there was probably a note next to his name to not bother calling again. Worst part of that six weeks was that when my wife took my son to college I could not go - my uncle pinch hit for me and drove them to the city.

You and I were, I think, in the same draft lottery - spring 1970 - as I think they did 2 years at once to start? Anyway, that was maybe a month before I was commissioned - I was signed, sealed and delivered to the US Army. I drew number 342 as I recall, my roommate was 350. We had a good laugh over that one.

I can't complain - like I said I was fortunate and had two great careers, one in the Army. Managed to do things and go places I never would have imagined. And I got to work with a lot of good people like that chief you ran into. And I was very blessed to have never had a class A accident or had to bury one of my soldiers.

Dale

Similar threads

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 573

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 598

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 478

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 947