ilovethevalley

Plastic

- Joined

- Jul 11, 2011

- Location

- Illinois, USA

Hi all,

I am cutting square channels into acrylic to create a microfluidic device. The channel depths vary from 0.800 mm to 0.200 mm. I solvent well this piece to a blank piece of acrylic to create the tops of the channels. Before the pieces are solvent welded together, I polish them (on a polishing wheel)to remove the tool marks from face milling. However, I have a tendency to round the corners and edges when polishing. This creates pieces that are less flat and do not bond completely toward the edge.

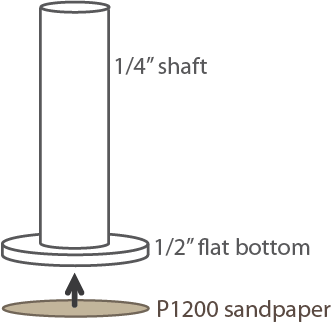

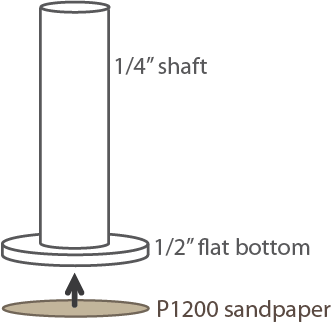

I would like to polish these while they are still clamped on the mill. I was thinking I could adhere fine sand paper to the bottom of a flat tool:

(Note: 1/4" is the largest shaft that can fit in my mill.)

I would use a low spindle speed (1000 RPM or 250 RPM if I use a reducing gear) and plenty of water and do a serpentine pass across the surface. My goal is to polish away the tool marks while still maintaining a flat surface. I'd like to have the flatness be within 0.10 mm (this is within the capabilities of my machine).

If the sand paper is stuck on even enough,the tool is flat enough and the machine's positional accuracy is good enough, do you think this will work?

I'm about a month away from actually trying this. But if anyone has tried this or has tips/concerns I'd like to hear about it. I post my results, good or bad.

I am cutting square channels into acrylic to create a microfluidic device. The channel depths vary from 0.800 mm to 0.200 mm. I solvent well this piece to a blank piece of acrylic to create the tops of the channels. Before the pieces are solvent welded together, I polish them (on a polishing wheel)to remove the tool marks from face milling. However, I have a tendency to round the corners and edges when polishing. This creates pieces that are less flat and do not bond completely toward the edge.

I would like to polish these while they are still clamped on the mill. I was thinking I could adhere fine sand paper to the bottom of a flat tool:

(Note: 1/4" is the largest shaft that can fit in my mill.)

I would use a low spindle speed (1000 RPM or 250 RPM if I use a reducing gear) and plenty of water and do a serpentine pass across the surface. My goal is to polish away the tool marks while still maintaining a flat surface. I'd like to have the flatness be within 0.10 mm (this is within the capabilities of my machine).

If the sand paper is stuck on even enough,the tool is flat enough and the machine's positional accuracy is good enough, do you think this will work?

I'm about a month away from actually trying this. But if anyone has tried this or has tips/concerns I'd like to hear about it. I post my results, good or bad.