17th Century Lens-Lathing

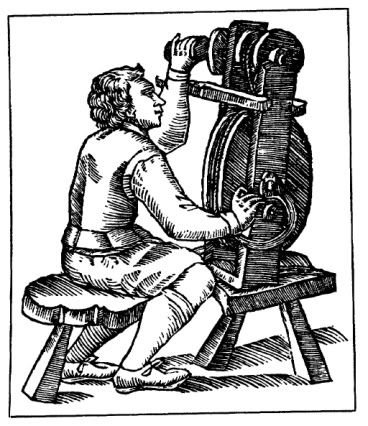

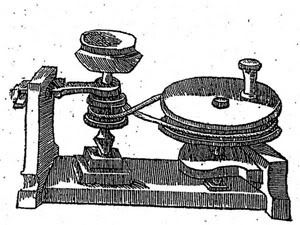

I am hoping to find someone who knows something about the history of 17th century lathes. I am looking into the possible construction of the philosopher Spinoza's lathe. Some may not know that the famous rationalist Dutch philosopher was a grinder of lenses, and a builder of microscopes and telescopes. I am attempting to make much more clear the kind of mechanism he likely used.

If anyone has an expertise in this area help would certainly be appreciated.

The issues of interest are these:

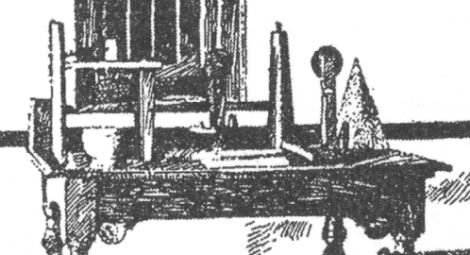

1. There is at the Spinoza museum in Rijnsburg a reproduction of a 17th century lathe. Some pictures of it can be found here and here, on my weblog. If any one can identfy the type of lathe this likely is, this would be wonderful. (The authenticity of this lathe I cannot establish.)

A sample:

2. I have read much on the history of the lens-grindling lathe at this period. The difficulty is that most of the texts are about experimental models being made by savants. I still do not have a sense of exactly what the average lens craftsman would be doing? For instance, would a blacksmith cast the "forms" for lens-grinding? What trade guilds ruled spectacle production in Holland? If anyone has a vivid sense of the state of the art of lathing for optical glass, from metal forms to finished glass, I would value their opinion.

3. I have also come to the realization that as Spinoza did not likely learn his trade from Guilded Spectacle Makers, he may very well have learned it from diamond polishers in his community. If anyone has any knowledge of the kinds of gem polishing lathes, and techniques that were being used in the 1650''s in Amsterdam, or any ideas for sources on these facts, this would be of great help. Spinoza is known to have been quite adept at polishing his lenses, something that was admired by some of the most brilliant craftsmen of his time, and it may very well be that by using gem-polishing techniques he had advantages that other lens-grinders may not have had.

Thanks in advance for any thoughts that might be given. Here are my weblog on the issue of how Spinoza's lathe-work may have influenced his philosophy:Frames /sing: Spinoza's Foci

I am hoping to find someone who knows something about the history of 17th century lathes. I am looking into the possible construction of the philosopher Spinoza's lathe. Some may not know that the famous rationalist Dutch philosopher was a grinder of lenses, and a builder of microscopes and telescopes. I am attempting to make much more clear the kind of mechanism he likely used.

If anyone has an expertise in this area help would certainly be appreciated.

The issues of interest are these:

1. There is at the Spinoza museum in Rijnsburg a reproduction of a 17th century lathe. Some pictures of it can be found here and here, on my weblog. If any one can identfy the type of lathe this likely is, this would be wonderful. (The authenticity of this lathe I cannot establish.)

A sample:

2. I have read much on the history of the lens-grindling lathe at this period. The difficulty is that most of the texts are about experimental models being made by savants. I still do not have a sense of exactly what the average lens craftsman would be doing? For instance, would a blacksmith cast the "forms" for lens-grinding? What trade guilds ruled spectacle production in Holland? If anyone has a vivid sense of the state of the art of lathing for optical glass, from metal forms to finished glass, I would value their opinion.

3. I have also come to the realization that as Spinoza did not likely learn his trade from Guilded Spectacle Makers, he may very well have learned it from diamond polishers in his community. If anyone has any knowledge of the kinds of gem polishing lathes, and techniques that were being used in the 1650''s in Amsterdam, or any ideas for sources on these facts, this would be of great help. Spinoza is known to have been quite adept at polishing his lenses, something that was admired by some of the most brilliant craftsmen of his time, and it may very well be that by using gem-polishing techniques he had advantages that other lens-grinders may not have had.

Thanks in advance for any thoughts that might be given. Here are my weblog on the issue of how Spinoza's lathe-work may have influenced his philosophy:Frames /sing: Spinoza's Foci