A lot of thought packed into a few moving parts. Large mass and high energy require a lot of attention and respect.

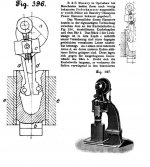

That's true! There were a lot of other mechanical hammer designs, hundreds in fact in the US over time- this stands out as one of the very best for a few reasons. The frame, unlike many of the Little Giant/Champion/Fairbanks types, is much more akin to a single steam hammer frame, such as the early Rigby, Massey, Chambersburg, or Niles Bement hammers... a square, tapering arch with the ram guides cast in massively befitting their importance, with heavy adjustability built in. So too, with the two piece design. This is certainly found in heavier mechanical hammers of other makes, but the orientation of the long axis of the dies on the Beaudry makes more sense to me, considering the direction of rotation of all the spinning mass in the power train. There's less side-kick to the stroke if the guides are not perfectly tight, and I'd think less wear and strain on moving parts with the rotary and reciprocating movements co-planar with each other and with the long axis of the dies.

The common problem found by hammer designers was how to provide for longer stock to clear the frame during forging- often the answer arrived at borrowed from Massey or Niles design, just turning the dies 20-30 degrees out of line with the main frame standard. Great for a steam hammer, with no rotary mass above being converted to reciprocating motion... On a Beaudry, the dies are inline with, but offset from, the main standard. The least attractive solution, to my mind, is that found on early Little Giants as well as the Bradley Compact and DuPont Fairbanks hammers, that of a hole through the frame in line with the dies.

Also the brake, being an integral part of the design, is quite robust and works very well. This gives comparatively excellent control. Not only is the ram height adjustable, but so is the stroke length, which many mech hammers fail to provide.

The spring-ram system of the linkage is ingenious, in that it's extremely robust as well as eliminating a lot of the wear points one sees with DuPont type linkages- in which all too often the necessary maintenance consists of directly oiling all of the friction points. Not only that, but the tension of the linkage is easily and symmetrically adjustable- the lack of which consideration is another common failing in lesser designs.

If I had to gripe about one thing, it's that Beaudry skimped a little bit on the weight of their anvil/sow in relation to the tup weight of the hammer. You really have to bolt the anvil down hard on quite a good foundation to get it not to move. One always sees these set up with tons of wood wedges in the gap between anvil and frame- later models had an included steel ring to take up the space, which I'm thinking of studying and fabricating for my own hammer.

In my case, I set the hammer and anvil down together on a gasket pad of 1-1/8" plywood. This causes some bounce currently, as the wood under the anvil is in the process of crushing. If this does not improve over time, perhaps I will go as far as jacking and blocking the machine up an inch or two, removing the ply from under the anvil base, and retrofitting Fabreeka shock mat in there. I'd have done that to begin with, but the price on that stuff is a bit shocking and wasn't in the reasonable budget...