dgfoster

Diamond

- Joined

- Jun 14, 2008

- Location

- Bellingham, WA

Well, my 36" light weight ductile cast iron straight edge is coming along nicely. It is scraped to 20 PPI. After casting it was stress relieved once by slow cooling in the mold (yes that is legit) and then again stress relieved at 1200 degrees for one hour followed by a 12 hour cool down to 300 degrees. This must have been effective as SE printed consistently throughout the many hand scraping cycles. I scraped off 2.5 ounces of metal in the process. The good news is that did bring her weight down to 20 pounds two ounces.

To see pics please go to post 129 of http://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/general/how-straight-straight-edges-284745/index7.html I decided to start fresh with a new thread here for reasons that are probably apparent.

That may not sound like much metal scraped off but seemed like plenty for hand scraping. Next time I will use what i learned to do a more refined job of machining so there is not so much metal to scrape. Since my mill has only 23" of travel on its 42" bed, I made two setups to get the full of the SE. Someone pointed out I could have/should have just mounted it to my table and swung the column to reach the full 36" without making a new setup. I think that would reduce the inevitable error in setup and thus required less scraping. I will also say that after discussion with a materials science person, I used a corn cob rougher rather than a typical spiral flute end mill as the nubs of the rougher plow through the material rather than slice it. This should result in less hidden stresses in the SE following machining compared to using a spiral flute EM. The obvious trade off is the corn cob leaves a fairly corrugated surface and so more scraping is required.

Another lesson learned was the value of a filing the SE in conjunction with scraping. An experienced scraper hand, after listening to me whine off-line about the amount of material to be removed, suggested using a coarse file to very carefully file down to just about eliminate scraping marks as a cycle in scraping and then scrape down to just about eliminate the file scratches. This had to be done carefully to avoid round-over of the edge but did allow very rapid removal of metal (a thou in just one file/scrape cycle) which probably save 3 cycles of scraping for me. For me, filing at about a 20 30 degree off-longitudinal-SE-axis stroke of the file helped prevent round over. NEXT TIME after finishing with the rougher I will use the file first to get nearly get rid of the machining marks left by the EM and then start scraping. I will then not hesitate to get out the file for areas that may be very high as a quick way to lower them. I was hesitant (but fatigue can wear down your will to resist ;-) ) to follow his advice to use the file as I was afraid of raising hell with the print. But I found that this was not the case. In just a couple of cycles my print was back as good as it was before the filing process. It was being mindful of the scratch depth and scraping mark depth that kept me "on the level."

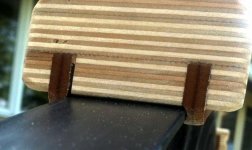

I am presently close to completing work on insulating handles that, like the SE itself, are somewhat innovative to the best of my knowledge. I will post more about that in a day or two in the spirit of sharing ideas for the general good.

My thanks to those who have offered useful advice and encouragement so far.

I am hoping this thread can avoid some of the controversial comments that plagued the old thread. So, if people have on-topic questions or helpful suggestions please feel free to offer them.

Denis

To see pics please go to post 129 of http://www.practicalmachinist.com/vb/general/how-straight-straight-edges-284745/index7.html I decided to start fresh with a new thread here for reasons that are probably apparent.

That may not sound like much metal scraped off but seemed like plenty for hand scraping. Next time I will use what i learned to do a more refined job of machining so there is not so much metal to scrape. Since my mill has only 23" of travel on its 42" bed, I made two setups to get the full of the SE. Someone pointed out I could have/should have just mounted it to my table and swung the column to reach the full 36" without making a new setup. I think that would reduce the inevitable error in setup and thus required less scraping. I will also say that after discussion with a materials science person, I used a corn cob rougher rather than a typical spiral flute end mill as the nubs of the rougher plow through the material rather than slice it. This should result in less hidden stresses in the SE following machining compared to using a spiral flute EM. The obvious trade off is the corn cob leaves a fairly corrugated surface and so more scraping is required.

Another lesson learned was the value of a filing the SE in conjunction with scraping. An experienced scraper hand, after listening to me whine off-line about the amount of material to be removed, suggested using a coarse file to very carefully file down to just about eliminate scraping marks as a cycle in scraping and then scrape down to just about eliminate the file scratches. This had to be done carefully to avoid round-over of the edge but did allow very rapid removal of metal (a thou in just one file/scrape cycle) which probably save 3 cycles of scraping for me. For me, filing at about a 20 30 degree off-longitudinal-SE-axis stroke of the file helped prevent round over. NEXT TIME after finishing with the rougher I will use the file first to get nearly get rid of the machining marks left by the EM and then start scraping. I will then not hesitate to get out the file for areas that may be very high as a quick way to lower them. I was hesitant (but fatigue can wear down your will to resist ;-) ) to follow his advice to use the file as I was afraid of raising hell with the print. But I found that this was not the case. In just a couple of cycles my print was back as good as it was before the filing process. It was being mindful of the scratch depth and scraping mark depth that kept me "on the level."

I am presently close to completing work on insulating handles that, like the SE itself, are somewhat innovative to the best of my knowledge. I will post more about that in a day or two in the spirit of sharing ideas for the general good.

My thanks to those who have offered useful advice and encouragement so far.

I am hoping this thread can avoid some of the controversial comments that plagued the old thread. So, if people have on-topic questions or helpful suggestions please feel free to offer them.

Denis