Joe Michaels

Diamond

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2004

- Location

- Shandaken, NY, USA

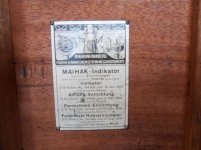

While the subject of steam engine indicators is a bit off topic from machine tools, it has come up at some length on this 'board from time to time. I own two (2) of the "classic" indicators, ca 1900-1920, complete in the wood cases and with reducing motions and assorted springs. While I have not "taken cards" on a steam engine in years, I still appreciate the steam engine indicators as a fine instrument. Years ago, on a job with the late Mike Korol, the Skinner erector, we took cards on some Filer & Stowell 4 valve engines. Mike had a Bachrach indicator in a fiberboard case, and described it as a "Maihak" type instrument. I was impressed with that indicator- a lot more rigid than the lighter "classic" indicators of the 1900-1920's. Mike passed along his indicator to someone else, and eventually passed on from this life.

A few weeks ago, I was browsing around the web and found a steam site called Discover Steam (IIRC), with classified ads and reasonable prices for all manner of steam related items including launch engines, railroad items, etc. One item was a lot of five Bachrach indicators, one hundred dollars apiece or $425 for the lot. The photos showed a complete instrument in the gray fiberboard case, as Mike Korol had used. One hundred bucks for a Bachrach indicator is dirt cheap as "classic" steam engine indicators on eBay seem to be (at least in the seller's eye) worth $1000 apiece. I contacted the seller of the Bachrach indicators and he said the lot of five was bespoken for, but would pass my name along to the buyer. The buyer of the 5 indicators agreed to sell me one, for which I paid 300 bucks including shipping from Canada.

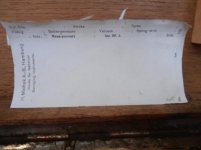

The instrument arrived and it was in excellent shape, well cared for. Even a nickel-plated "made in USA" small oil can with spout cap was in the case, as were all the appropriate wrenches, glass tube of pencil points and pad of indicator paper with Bachrach's name and address on it. There were several springs for the indicator, but all were for the same pressure range, which has a scale of 3mm = 1 atm (14.6 psi), maximum being 240 psi.

The range of the springs and the fact the springs were all the same range got me to thinking, wondering where the indicator had been used. I contacted Bachrach to see if they had a manual and lower pressure range springs. Their engineer said in 36 years he'd been with Bachrach, he had never seen one of their engine indicators, and no one was left at Bachrach who knew anything about them, nor had they any springs or a manual.

Reasoning that the indicator was a Maihak (German) design, I quickly discovered Leutert, of Germany, still makes that same style indicator. I contacted Leutert, who were quite prompt and helpful. Unfortunately, while they took over the Maihak indicator manufacture, they now only build them for indicating large marine diesel engines. No lower range springs available, and their instruments are made with a much smaller piston diameter than for indicating steam engines. Leutert did send me a manual, on line, in English.

It was time to get the indicator ready to go to work, come spring, up at Hanford Mills. I removed the union gland nut from the indicator, discovering it was held in place on the male cone by loose ball bearings put in through a setscrew hole and filling two half-spherical grooves- similar to packing a ball bearing assembly.

Once I had the union apart, I was able to measure the taper on the male cone. I was also able to measure the threads on a male threaded indicator "holder" fastened on the case for holding the indicator when changing springs or similar. The thread was an eye-opener. Figuring it to be metric, I miked the OD and came up with 27 mm with a few thousandths clearance on the OD. I then tried a metric screw pitch gauge on the thread and came up with 2,5 mm pitch. Some math disclosed this to be with 0.002" of a pitch of 10 threads per inch. A 10 threads/inch pitch gauge fit as well. I checked with Leutert: their indicator cocks have a the strange thread of 27 MM x 1/10".

Making a matching adaptor to connect to the union on the indicator and connect to 1/2" tapered pipe threads is no big deal. The higher pressure rating on the spring, and the fact there were five indicators all with the same spring rating in the lot had me thinking. My reasoning was the higher pressure range on the springs would be consistent with a marine Unaflow steam engine. The fact there were five indicators in the lot, all the same, supported this thinking. Marine unaflow steam engines were built in multiple cylinder designs, all cylinders the same diameter (except on the steeple compound versions).

One evening, as I was heading upstairs from my shop, I saw the fluorescent lighting reflecting off the lid of the Bachrach indicator case. Some faint printing was showing up. I looked closer, and faintly stamped into the lid was: "SS Prince George Eng Rm" I googled the SS Prince George and discovered there had been two ships of that name, both being operated by the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada. The later of the two Prince Georges had two Unaflow engines of 6 cylinders apiece, 3000 HP, running on (IIRC) 240 psig steam. Mystery of where the indicator came from was solved. The Prince George with the Unaflow engines went into service in 1947 and was in service at least into the 1970's. She then went into a spiraling decline and wound up a derelict hulk and was burned and scrapped, maybe in the 1990's. How the indicators made it out of the Prince George's engine room is anyone's guess. My guess is the first guy to have the indicators had six of them, one for each cylinder of a main Unaflow engine for taking cards simultaneously. That guy perhaps kept one indicator and put the remaining five up for sale, and the guy I got my indicator from obviously sold one to me, leaving him with four. He said via email that they wanted to indicated some traction engines and a locomotive.

As for my indicator, I plan to use it as it is. I took it apart, cleaned the old cylinder oil off the piston and cylinder (Hoppe's Number 9 gun bore cleaner), and put it back together. It is an extremely well made instrument, a lot more to it than the old "classic" indicators.

As for the higher pressure range of the spring, I can address this in a way not available to the oldtimers. If the card is too small to easily work my planimeter on, I can simply enlarge the card on a copy machine. With the atmospheric line and admission lines drawn on the card, and a gauge at each indicator tapping, I will be able to get the scale on the enlarged diagram for the pressure. The stroke will also be scaled off the card. I have a couple of reducing mechanisms from the old classic indicators, so making a bracket to use one of them is no problem.

The springs for the Bachrach or Maihak indicators use a double lead spring. There are two coils, wound in the same manner as a double lead thread, from one piece of spring wire. The top end of this spring wire is bent to span the diameter of the spring, and engages a slotted rod. The bottom of the spring is silver brazed to a base nut which has relieved steps, much like a ratchet, meeting the helix angle of the spring coils. Not an easy spring to duplicate !

The Hanford Mills engine runs at 200 rpm, and when we took cards with one of the old "classic" indicators, the diagram looked OK, but the lines showed a consistent fine "sawtooth" or jaggedness throughout the diagram. My guess is the indicator (brought by another guy) had some lost motion in mechanism for the pencil, and possibly some flexure in the frame.

Meanwhile, I am quite pleased with the Bachrach indicator, and knowing its history makes it a bit more special. The Unaflow engines in the "Prince George" were likely built to Skinner's design by a Canadian firm (Canadian Vickers, I think). I am sure some of our Canadian brethren will have some familiarity with the "Prince George".

A few weeks ago, I was browsing around the web and found a steam site called Discover Steam (IIRC), with classified ads and reasonable prices for all manner of steam related items including launch engines, railroad items, etc. One item was a lot of five Bachrach indicators, one hundred dollars apiece or $425 for the lot. The photos showed a complete instrument in the gray fiberboard case, as Mike Korol had used. One hundred bucks for a Bachrach indicator is dirt cheap as "classic" steam engine indicators on eBay seem to be (at least in the seller's eye) worth $1000 apiece. I contacted the seller of the Bachrach indicators and he said the lot of five was bespoken for, but would pass my name along to the buyer. The buyer of the 5 indicators agreed to sell me one, for which I paid 300 bucks including shipping from Canada.

The instrument arrived and it was in excellent shape, well cared for. Even a nickel-plated "made in USA" small oil can with spout cap was in the case, as were all the appropriate wrenches, glass tube of pencil points and pad of indicator paper with Bachrach's name and address on it. There were several springs for the indicator, but all were for the same pressure range, which has a scale of 3mm = 1 atm (14.6 psi), maximum being 240 psi.

The range of the springs and the fact the springs were all the same range got me to thinking, wondering where the indicator had been used. I contacted Bachrach to see if they had a manual and lower pressure range springs. Their engineer said in 36 years he'd been with Bachrach, he had never seen one of their engine indicators, and no one was left at Bachrach who knew anything about them, nor had they any springs or a manual.

Reasoning that the indicator was a Maihak (German) design, I quickly discovered Leutert, of Germany, still makes that same style indicator. I contacted Leutert, who were quite prompt and helpful. Unfortunately, while they took over the Maihak indicator manufacture, they now only build them for indicating large marine diesel engines. No lower range springs available, and their instruments are made with a much smaller piston diameter than for indicating steam engines. Leutert did send me a manual, on line, in English.

It was time to get the indicator ready to go to work, come spring, up at Hanford Mills. I removed the union gland nut from the indicator, discovering it was held in place on the male cone by loose ball bearings put in through a setscrew hole and filling two half-spherical grooves- similar to packing a ball bearing assembly.

Once I had the union apart, I was able to measure the taper on the male cone. I was also able to measure the threads on a male threaded indicator "holder" fastened on the case for holding the indicator when changing springs or similar. The thread was an eye-opener. Figuring it to be metric, I miked the OD and came up with 27 mm with a few thousandths clearance on the OD. I then tried a metric screw pitch gauge on the thread and came up with 2,5 mm pitch. Some math disclosed this to be with 0.002" of a pitch of 10 threads per inch. A 10 threads/inch pitch gauge fit as well. I checked with Leutert: their indicator cocks have a the strange thread of 27 MM x 1/10".

Making a matching adaptor to connect to the union on the indicator and connect to 1/2" tapered pipe threads is no big deal. The higher pressure rating on the spring, and the fact there were five indicators all with the same spring rating in the lot had me thinking. My reasoning was the higher pressure range on the springs would be consistent with a marine Unaflow steam engine. The fact there were five indicators in the lot, all the same, supported this thinking. Marine unaflow steam engines were built in multiple cylinder designs, all cylinders the same diameter (except on the steeple compound versions).

One evening, as I was heading upstairs from my shop, I saw the fluorescent lighting reflecting off the lid of the Bachrach indicator case. Some faint printing was showing up. I looked closer, and faintly stamped into the lid was: "SS Prince George Eng Rm" I googled the SS Prince George and discovered there had been two ships of that name, both being operated by the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada. The later of the two Prince Georges had two Unaflow engines of 6 cylinders apiece, 3000 HP, running on (IIRC) 240 psig steam. Mystery of where the indicator came from was solved. The Prince George with the Unaflow engines went into service in 1947 and was in service at least into the 1970's. She then went into a spiraling decline and wound up a derelict hulk and was burned and scrapped, maybe in the 1990's. How the indicators made it out of the Prince George's engine room is anyone's guess. My guess is the first guy to have the indicators had six of them, one for each cylinder of a main Unaflow engine for taking cards simultaneously. That guy perhaps kept one indicator and put the remaining five up for sale, and the guy I got my indicator from obviously sold one to me, leaving him with four. He said via email that they wanted to indicated some traction engines and a locomotive.

As for my indicator, I plan to use it as it is. I took it apart, cleaned the old cylinder oil off the piston and cylinder (Hoppe's Number 9 gun bore cleaner), and put it back together. It is an extremely well made instrument, a lot more to it than the old "classic" indicators.

As for the higher pressure range of the spring, I can address this in a way not available to the oldtimers. If the card is too small to easily work my planimeter on, I can simply enlarge the card on a copy machine. With the atmospheric line and admission lines drawn on the card, and a gauge at each indicator tapping, I will be able to get the scale on the enlarged diagram for the pressure. The stroke will also be scaled off the card. I have a couple of reducing mechanisms from the old classic indicators, so making a bracket to use one of them is no problem.

The springs for the Bachrach or Maihak indicators use a double lead spring. There are two coils, wound in the same manner as a double lead thread, from one piece of spring wire. The top end of this spring wire is bent to span the diameter of the spring, and engages a slotted rod. The bottom of the spring is silver brazed to a base nut which has relieved steps, much like a ratchet, meeting the helix angle of the spring coils. Not an easy spring to duplicate !

The Hanford Mills engine runs at 200 rpm, and when we took cards with one of the old "classic" indicators, the diagram looked OK, but the lines showed a consistent fine "sawtooth" or jaggedness throughout the diagram. My guess is the indicator (brought by another guy) had some lost motion in mechanism for the pencil, and possibly some flexure in the frame.

Meanwhile, I am quite pleased with the Bachrach indicator, and knowing its history makes it a bit more special. The Unaflow engines in the "Prince George" were likely built to Skinner's design by a Canadian firm (Canadian Vickers, I think). I am sure some of our Canadian brethren will have some familiarity with the "Prince George".