A few comments to amplify those that have been mentioned regarding the broken teeth on the spindle gear.

There are a variety of methods to do this, including the one mentioned (which was to braze up and then re-cut the teeth, using

support pins embedded in the braze).

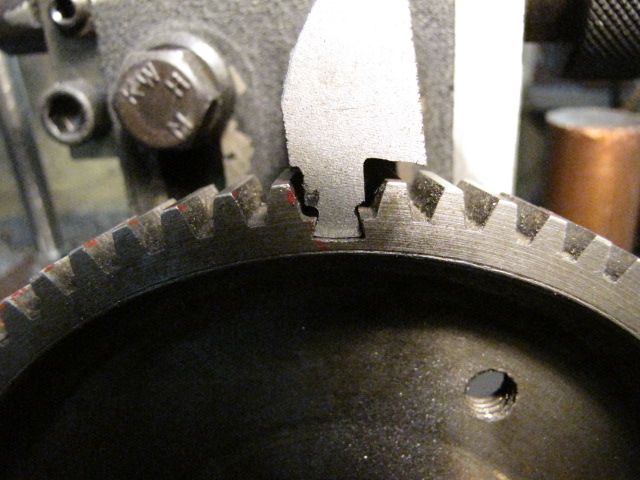

1) Replace the missing tooth with steel pins pressed into the casting, and profile the pins to act as a tooth.

2) undercut the region of the gear with a slot where the tooth is missing, and silver solder in a steel or cast iron

slug, which is then cut into a tooth with an involute gear cutter.

3) fabricate an entirely new gear to replace the one missing teeth.

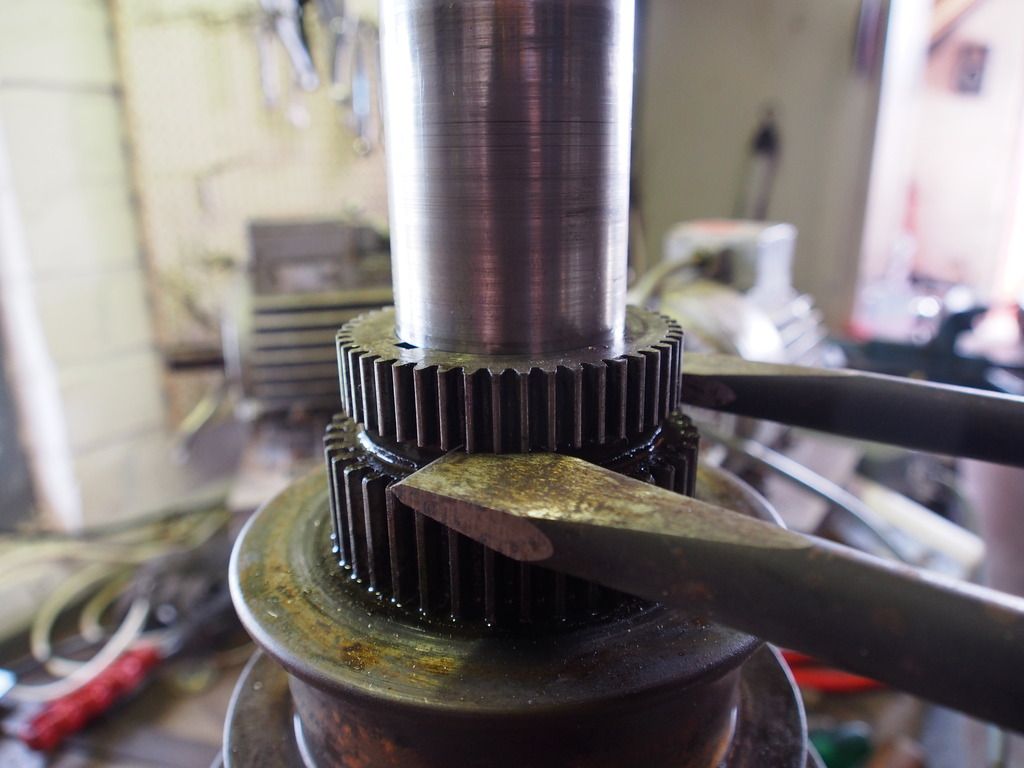

Here's an example from my elderly seneca falls lathe, where the former owner had done the first fix:

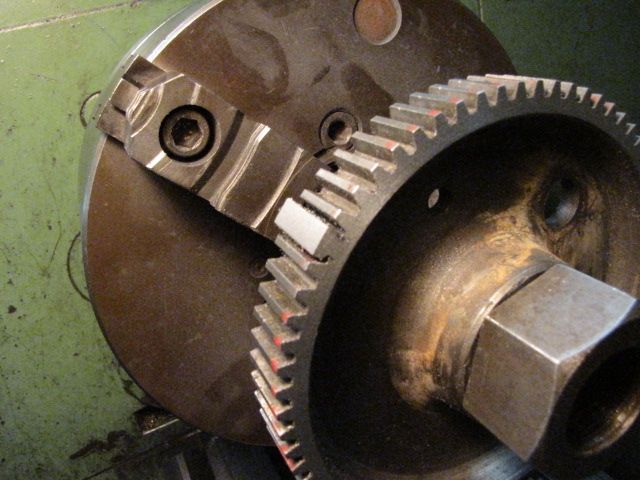

In this case I chose to re-make this gear from scratch as it was not too large, could

be made of steel, and had several missing teeth:

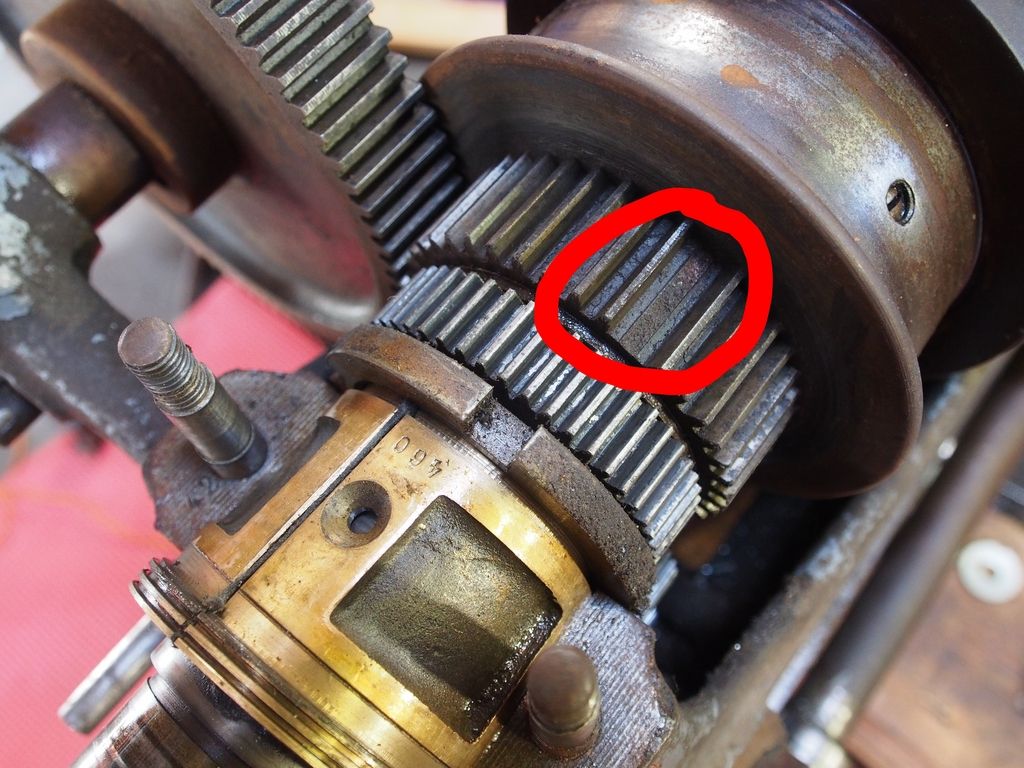

The gear that was replaced is the outboard one on the end of the spindle. Notice

the back gear that larger and mounted to the cone pulley, is also missing teeth.

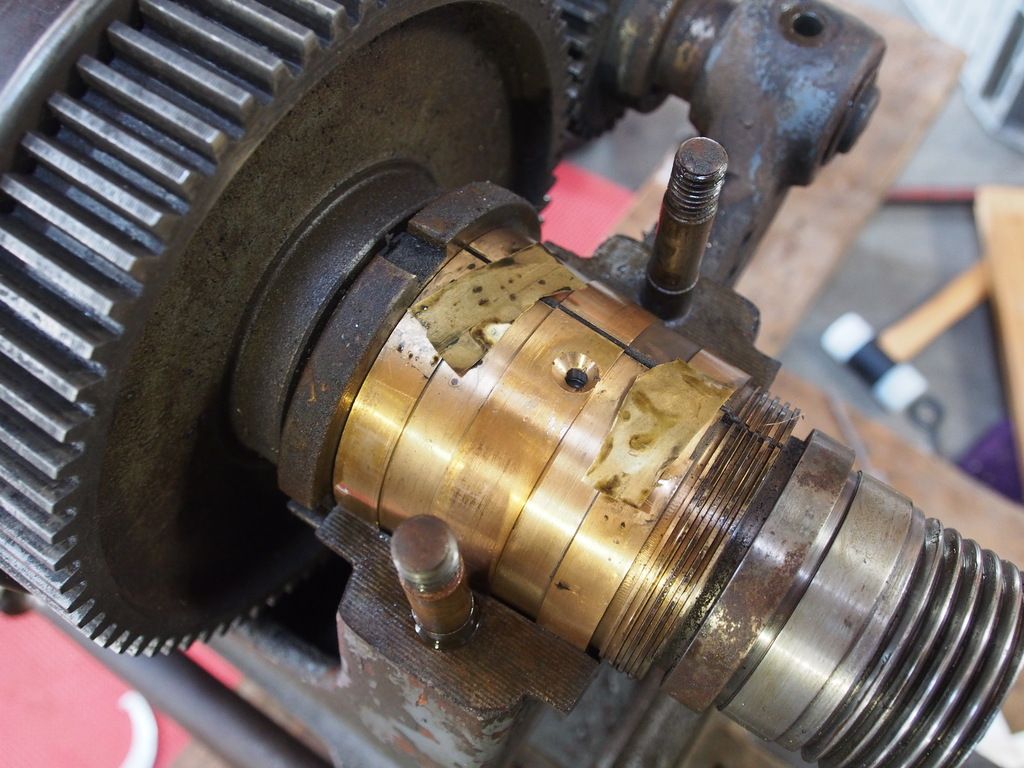

I eventually did purchase some cast iron bar stock and re-made that gear as well, which

was a tougher job as it has a long boss on it that presses into the body of the cone pulley.

If you have access to a milling machine and a dividing head, it really is not that tough a job

to re-manufacture a gear like this. The involute cutters are a very modest expense if you can

find the one that you need for your gearing system.

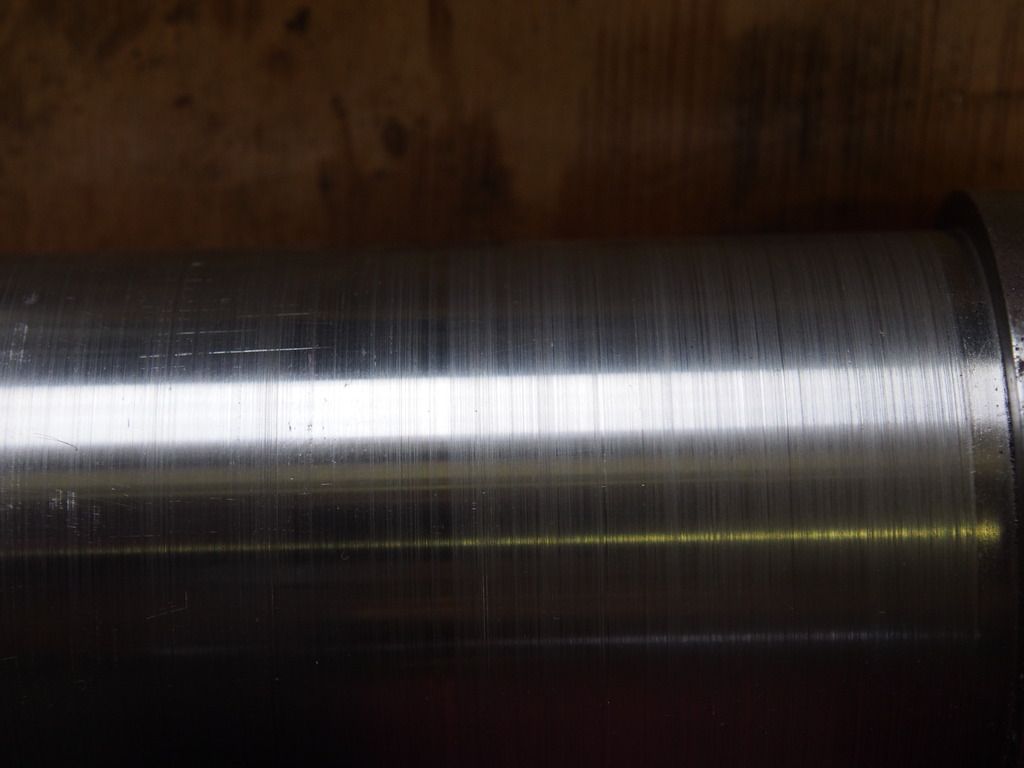

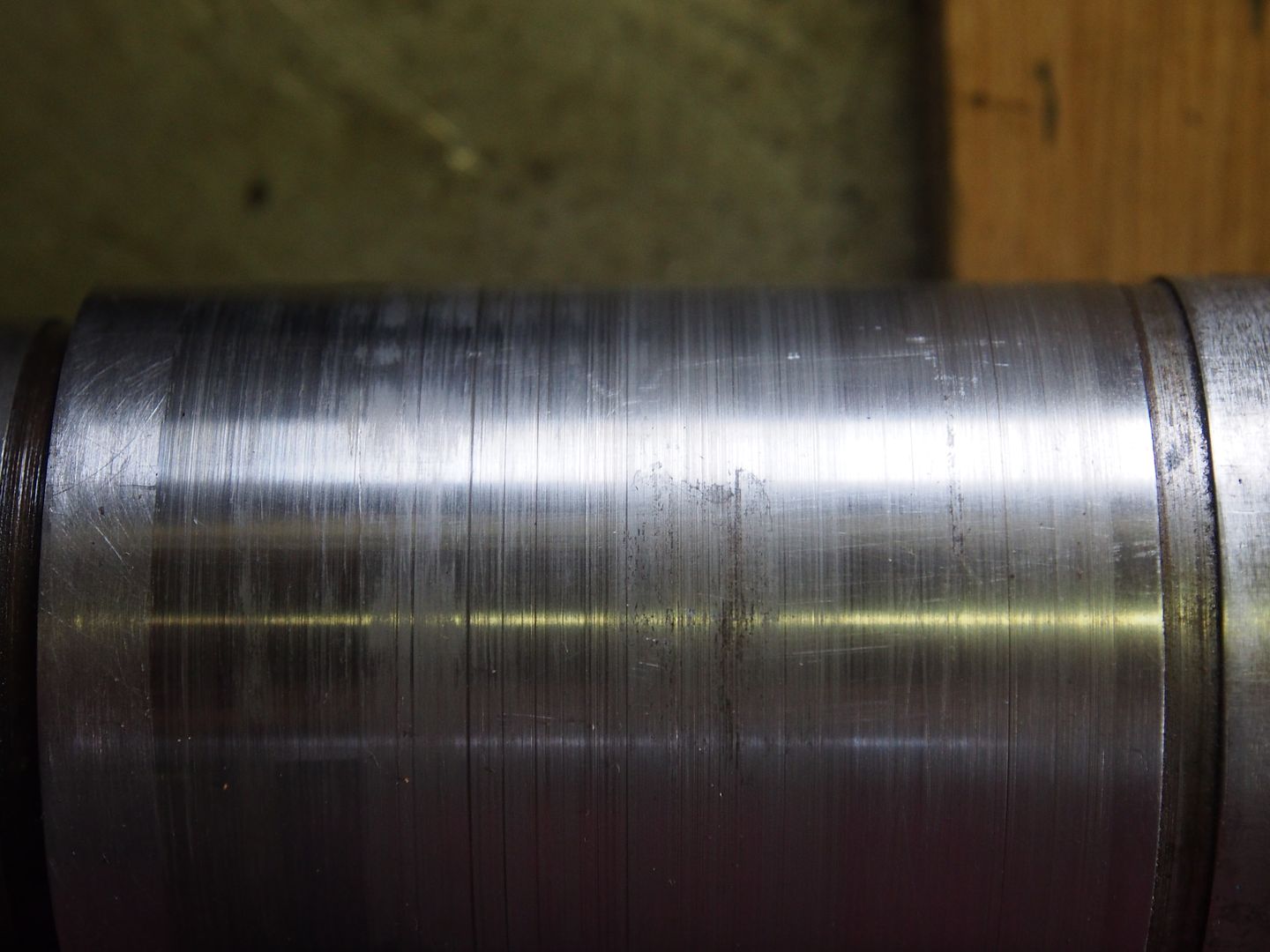

When I saw those journal and bearing surfaces I thought, that's it, game over! But now that I've read your posting I've decided to push on and see if I can get this thing running. After all, I've already got a motor and vfd. Also, the new workbench is nearly finished.

When I saw those journal and bearing surfaces I thought, that's it, game over! But now that I've read your posting I've decided to push on and see if I can get this thing running. After all, I've already got a motor and vfd. Also, the new workbench is nearly finished.

![IMG_2045[1].jpg IMG_2045[1].jpg](https://www.practicalmachinist.com/forum/data/attachments/157/157206-fbfac22c6b4434eb519937958e37a2f2.jpg)

![IMG_2046[1].jpg IMG_2046[1].jpg](https://www.practicalmachinist.com/forum/data/attachments/157/157207-41859dae41b1d0fc1aea2ff0d426a274.jpg)

![IMG_2047[1].jpg IMG_2047[1].jpg](https://www.practicalmachinist.com/forum/data/attachments/157/157208-bc210e6f75625bfac6672c6d2bd33ccb.jpg)

![IMG_2103[1].jpg IMG_2103[1].jpg](https://www.practicalmachinist.com/forum/data/attachments/157/157209-aefefd1cbb4be79a79769be871504808.jpg)

![IMG_2239[1].jpg IMG_2239[1].jpg](https://www.practicalmachinist.com/forum/data/attachments/157/157210-1671c3f334f97cef4ee3fbcae92c7228.jpg)